Sometimes a wound is so deep and unhealed that I can’t stop myself from trying to understand what it all means. One only has to look at the images of the Confederate flag being carried into the U.S. Capitol last January 6th to know this war has not gone away.

“This war” is, of course, the American Civil War. In 2021, I again read books looking at “this mighty scourge,” as Lincoln called it in his second inaugural. I recorded a brief video at William Faulkner’s home. I quoted him, “For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863” (Intruder in the Dust, 1948). I was that lad growing up in the Deep South. I knew Pickett’s charge on the third day at Gettysburg was the “high water mark” of the Confederate nation.

I started my review of my 2021 reading with spiritual books and then books on science. Here are my Civil War reads:

Grant (2017) By Ron Chernow

I listened to all 48 hours of this 900+ page book. It was worth every minute. Grant overcame so many setbacks to succeed as a general and President. Most significantly, according to Chernow, was his conquering his struggles with alcohol, a fact he does not mention in his own memoir. Had the Civil War never happened, history might not have known the name of U.S. Grant. It was his strategy to cut off the Southern states from beyond the Mississippi River with the fall of Vicksburg (July 1863), send Sherman through Georgia (1864), and capture Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. There was no finer moment in his life than when he offered generous terms of surrender to Lee. He hoped to begin the healing of a fractured nation. Sadly, as President, he had to fight the South again as it rose in the K.K.K. We are fortunate, as a nation, that Grant and Lincoln rose to the top when we needed them.

I listened to all 48 hours of this 900+ page book. It was worth every minute. Grant overcame so many setbacks to succeed as a general and President. Most significantly, according to Chernow, was his conquering his struggles with alcohol, a fact he does not mention in his own memoir. Had the Civil War never happened, history might not have known the name of U.S. Grant. It was his strategy to cut off the Southern states from beyond the Mississippi River with the fall of Vicksburg (July 1863), send Sherman through Georgia (1864), and capture Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. There was no finer moment in his life than when he offered generous terms of surrender to Lee. He hoped to begin the healing of a fractured nation. Sadly, as President, he had to fight the South again as it rose in the K.K.K. We are fortunate, as a nation, that Grant and Lincoln rose to the top when we needed them.

Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause (2021) By Ty Seidule

Author Ty Seidule was born on July 3rd into a family culture steeped in the myth of righteous cause for which we Southerners fought. When people said, “too bad you weren’t born on the 4th,” he’d reply that he was glad to have been born on the day of Pickett’s charge (there it is again). Seidule rose through the ranks in the U.S. Army and taught at West Point. Through his academic research and soul-searching, he concluded that the “lost cause” myth of the South was wrong. According to Seidule, the Civil War was about slavery and the Confederate soldiers who took up arms against the U.S. government were traitors. He makes a compelling argument that we no longer need to honor these traitors with monuments or U.S. Army bases.

Author Ty Seidule was born on July 3rd into a family culture steeped in the myth of righteous cause for which we Southerners fought. When people said, “too bad you weren’t born on the 4th,” he’d reply that he was glad to have been born on the day of Pickett’s charge (there it is again). Seidule rose through the ranks in the U.S. Army and taught at West Point. Through his academic research and soul-searching, he concluded that the “lost cause” myth of the South was wrong. According to Seidule, the Civil War was about slavery and the Confederate soldiers who took up arms against the U.S. government were traitors. He makes a compelling argument that we no longer need to honor these traitors with monuments or U.S. Army bases.

In the Hands of Providence: Joshua L. Chamberlain and the American Civil War (1992) By Alice Rains Trulock

Like most, I knew of Chamberlain for only a few hours of his life on July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg. He commanded the 20th Maine at the extreme end of the Union line on Little Round Top. His troops were under repeated assault and running out of ammunition. Had he failed in defending his position, the entire U.S. Army on the field could have been destroyed in a flanking maneuver by the advancing Confederates. He ordered his men to fix bayonets, and they charged downhill, capturing more than 100 Southerners and saving the day. Many books and movies have captured this one moment. He was a college professor before the war. He became a college president and served four years as governor after returning to Maine. One other moving scene in Chamberlain’s military career was the last day of the war. He was the commander in charge of the ceremony at Appomattox, where the defeated rebels would surrender their arms. In the spirit that Grant set in the terms of surrender, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute their defeated foes, now countrymen once again.

Like most, I knew of Chamberlain for only a few hours of his life on July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg. He commanded the 20th Maine at the extreme end of the Union line on Little Round Top. His troops were under repeated assault and running out of ammunition. Had he failed in defending his position, the entire U.S. Army on the field could have been destroyed in a flanking maneuver by the advancing Confederates. He ordered his men to fix bayonets, and they charged downhill, capturing more than 100 Southerners and saving the day. Many books and movies have captured this one moment. He was a college professor before the war. He became a college president and served four years as governor after returning to Maine. One other moving scene in Chamberlain’s military career was the last day of the war. He was the commander in charge of the ceremony at Appomattox, where the defeated rebels would surrender their arms. In the spirit that Grant set in the terms of surrender, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute their defeated foes, now countrymen once again.

Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920 (1980, 2009) By Charles Reagan Wilson

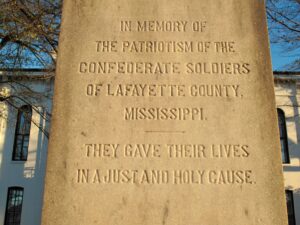

With all believing God is on their side in a war, it is especially hard for the losers to explain what happened. This presented an exceptional problem for the dominant version of Christianity in the South (evangelical Protestant). In their view, the Yankees were more secular, more liberal, more urban, and less devoted Christians. This book by Charles Wilson, a former professor at the University of Mississippi and fellow church member with me in Oxford, explains the mental and theological gymnastics my Southern ancestors went through to explain how God was on their side. God sided with the South because their cause was righteous, but the North’s industrial strength was too much even for God. Dr. Wilson recently gave three lectures on this topic at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Oxford, and they are on YouTube. If there is any doubt that Southerners saw their cause as God’s cause, you need to look no further than two blocks from where Dr. Wilson lectured at St. Peter’s. On the Confederate monument (1907) on the Square is the inscription “They gave their lives for a just and holy cause.”

With all believing God is on their side in a war, it is especially hard for the losers to explain what happened. This presented an exceptional problem for the dominant version of Christianity in the South (evangelical Protestant). In their view, the Yankees were more secular, more liberal, more urban, and less devoted Christians. This book by Charles Wilson, a former professor at the University of Mississippi and fellow church member with me in Oxford, explains the mental and theological gymnastics my Southern ancestors went through to explain how God was on their side. God sided with the South because their cause was righteous, but the North’s industrial strength was too much even for God. Dr. Wilson recently gave three lectures on this topic at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Oxford, and they are on YouTube. If there is any doubt that Southerners saw their cause as God’s cause, you need to look no further than two blocks from where Dr. Wilson lectured at St. Peter’s. On the Confederate monument (1907) on the Square is the inscription “They gave their lives for a just and holy cause.”

Fighting to defend slavery was “A JUST AND HOLY CAUSE.” Monument on the Square, Oxford, Mississippi

__________________________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

A

A

The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published an opinion piece,

The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published an opinion piece,

Last week,

Last week,  Rev. Lynn Casteel Harper of the Riverside Church in New York City, sees her role with congregants in their decline as one of “presence and witness.” “Sometimes if people are going through really difficult experiences, especially medically, it’s easy for the story of the illness and the suffering to take over,” Rev. Harper said. “Part of my role is to affirm the other dimensions.”

Rev. Lynn Casteel Harper of the Riverside Church in New York City, sees her role with congregants in their decline as one of “presence and witness.” “Sometimes if people are going through really difficult experiences, especially medically, it’s easy for the story of the illness and the suffering to take over,” Rev. Harper said. “Part of my role is to affirm the other dimensions.”

So, on Thanksgiving 1996, 42 years after his death, we had a funeral for my brother. Mom, Dad in his wheelchair, my brother, his wife, my daughter, and I gathered at the grave. I read the words of committal (“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”) and Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), we said the Lord’s Prayer, and I stammered through a prayer about Randy.

So, on Thanksgiving 1996, 42 years after his death, we had a funeral for my brother. Mom, Dad in his wheelchair, my brother, his wife, my daughter, and I gathered at the grave. I read the words of committal (“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”) and Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), we said the Lord’s Prayer, and I stammered through a prayer about Randy.