[Adapted from a chapter in Light in the Shadows by Hank.]

“This is where our struggle with dying starts,” was my first thought.

“Putting It Together”, J.D. Hillberry www.jdhillberry.com

Many summers ago, I was wandering through an arts festival in Crested Butte, Colorado, when I came across the works of an artist who made pencil drawings. I was fascinated by a sketch he had made of his two-year-old son, depicting him as an unfinished jigsaw puzzle.

The child is looking down at his hand, which appears to be emerging from the flat surface of the paper. There is a puzzle piece in his grasp. He is searching for the place where that piece of himself fits. The artist titled the picture “Putting It Together.”

This memory of that Colorado summer came as I am now, once again, hanging out with a toddler and his infant sibling. This is my third tour of duty caring for little humans. First, there were my children. Later, I provided daycare once a week for two of my grandchildren through their early years. Now, we occasionally watch a friend’s two sons, who are 18 months and four months old.

Toddlers and the “Denial of Death”

I was watching my two grands after reading Ernest Becker’s Pulitzer-Prize winning

Hank’s grandson learning control at the light switch

book, The Denial of Death. Now, under the influence of these two new little ones in my life, I am rereading Becker. His main thesis is that the prospect of death is THE driving force in human behavior. Both the building of our individual ego or self and our culture’s attempt to shield us from the horror of death’s finality. Here’s a sample:

“[A child] avoids [despair] by building defenses; and these defenses allow him to feel a basic sense of self-worth, of meaningfulness, of power. They allow him to feel that he controls his life and his death, that he really does live and act as a willful and free individual, that he has a unique and self-fashioned identity, that he is somebody.… We don’t want to admit that we are fundamentally dishonest about reality, that we do not really control our own lives.” (Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death. p 55.)

Play and learning to take control

The toddlers in my life have shown this behavior. I remember my grandson discovering the light switch. I would stand him on a chair, and he would play with the switch. He would flip it up and then jerk his head toward the ceiling to see the light appear. Then, down and the light goes off. His actions were affecting his environment.

Hank’s granddaughter and the “singing bowl”

Let a child play with a musical instrument. My grandchildren both loved to bang on the piano or hit my singing bowl with the mallet. Any noise accomplished their unconscious goal of finding out they could influence the world around them.

Even the delight I recently observed of our friend’s toddler playing with the garden hose in our backyard revealed a growing sense of self. He put his fingers in the nozzle and felt the water. He found he could direct the flow of water into the air or on me. He was gaining control.

Fortunately, gaining control of one’s life can be beneficial to everyone concerned. Eventually, the child learns that studying improves your grades. Exercise makes you feel better. Treating people kindly encourages them to return the kindness.

Even toward the end of life we can practice some control, choosing to seek a cure for a terminal disease or focus more on easing physical and spiritual pain.

Letting go of the illusions we created

Third tour of duty with little humans

Every child makes their own progress toward gaining a feeling of control. This positive self-image that gives us a sense of meaningfulness, safety, and stability, allows us to grow and thrive. What is truly happening is that WE are creating this ego with the material that is handed to us genetically and emotionally. If we do the job adequately, we can live a life enjoying emotional and spiritual health.

So why did the sketch of the child make me think, “This is where our struggle with dying starts”? One day, in the last phase of life, all this meticulously constructed personality we spent our whole lives creating is revealed for what it is — a mask. The root meaning of the words “person” and “personality” is from the Latin persona, a mask worn by actors in a play.

Last week I wrote about dying without illusions. Watch a toddler and see those illusions being created.

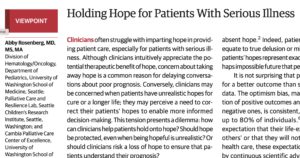

The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published an opinion piece,

The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published an opinion piece,

Last week,

Last week,  Rev. Lynn Casteel Harper of the Riverside Church in New York City, sees her role with congregants in their decline as one of “presence and witness.” “Sometimes if people are going through really difficult experiences, especially medically, it’s easy for the story of the illness and the suffering to take over,” Rev. Harper said. “Part of my role is to affirm the other dimensions.”

Rev. Lynn Casteel Harper of the Riverside Church in New York City, sees her role with congregants in their decline as one of “presence and witness.” “Sometimes if people are going through really difficult experiences, especially medically, it’s easy for the story of the illness and the suffering to take over,” Rev. Harper said. “Part of my role is to affirm the other dimensions.”

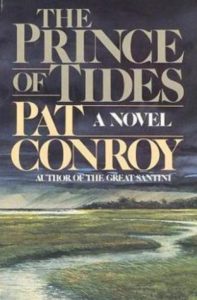

My wife, Sally, and I decided to watch the 1991 movie, The Prince of Tides, for a date night at home. I had forgotten how sad, tragic, yet hopeful the film was. The next day, having lunch with a friend, we mentioned we watched it. Our friend said, “That is my favorite movie.”

My wife, Sally, and I decided to watch the 1991 movie, The Prince of Tides, for a date night at home. I had forgotten how sad, tragic, yet hopeful the film was. The next day, having lunch with a friend, we mentioned we watched it. Our friend said, “That is my favorite movie.” It had been thirty years since we had seen it, and it was a little circuitous how The Prince of Tides came up on our radar. In researching the late Doug Marlette, creator of my favorite comic strip, Kudzu (

It had been thirty years since we had seen it, and it was a little circuitous how The Prince of Tides came up on our radar. In researching the late Doug Marlette, creator of my favorite comic strip, Kudzu ( So, on Thanksgiving 1996, 42 years after his death, we had a funeral for my brother. Mom, Dad in his wheelchair, my brother, his wife, my daughter, and I gathered at the grave. I read the words of committal (“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”) and Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), we said the Lord’s Prayer, and I stammered through a prayer about Randy.

So, on Thanksgiving 1996, 42 years after his death, we had a funeral for my brother. Mom, Dad in his wheelchair, my brother, his wife, my daughter, and I gathered at the grave. I read the words of committal (“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”) and Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), we said the Lord’s Prayer, and I stammered through a prayer about Randy.