Good question.

As people lose their memories, can no longer say who they are, can no longer recognize those closest to them … what’s left?

Blame it on the René Descartes

Blame it on the French. Well…actually, one Frenchman, René Descartes (1596-1650). He wanted to know, “What can I really know for sure?” His conclusion was, “I am thinking.” He then gave us, “I think, therefore I am.”

Fast forward to our effort to understand what is going on in the minds of dementia patients. These people are losing the ability to think. Eventually, they cannot recall the stories that made them who they became as adults. They cannot recall what they had for breakfast. They cannot tell you who they are.

So if Descartes is right, who are we when we can no longer think? Could we say, “If I don’t think, therefore, I am not”?

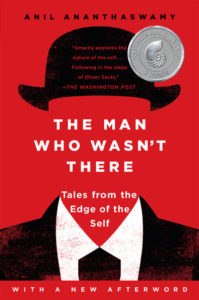

“Consider the phrases used [in the vast medical literature] to describe Alzheimer’s impact: ‘a steady erosion of selfhood,’ ‘unbecoming’ a self, ‘drifting towards the threshold of unbeing,’ and even ‘the complete loss of self.’” I got that sentence from a new book by Anil Ananthaswamy, The Man Who Wasn’t There: Investigations into the Strange New Science of the Self.

“Consider the phrases used [in the vast medical literature] to describe Alzheimer’s impact: ‘a steady erosion of selfhood,’ ‘unbecoming’ a self, ‘drifting towards the threshold of unbeing,’ and even ‘the complete loss of self.’” I got that sentence from a new book by Anil Ananthaswamy, The Man Who Wasn’t There: Investigations into the Strange New Science of the Self.

I just got back from speaking at an Alzheimer’s conference in Washington state. They wanted my standard talk based on my book Hard Choices for Loving People about making end-of-life decisions. I also had 90 minutes to talk about the emotional and spiritual issues at the end of life. Part of my lecture looked at the loss of the self.

But thinking is not all of who we are

Ananthaswamy’s book has a whole chapter dedicated to Alzheimer’s disease and the self. The chapter is 35 pages so I am looking at just one aspect of all this. It is true that much of what we consider “the self” is lost as dementia progresses. But thinking is not all of who we are. There is an embodied self, that literally is located in our physical body.

We learn to ride a bicycle as a child and do not ride again for 30 years. We don’t have to “think” about it. Our body knows how to ride again as an adult. Quick. Which finger do you use to type the letter “C” on the keyboard? Perhaps you could not tell me which it is but could immediately type it “without thinking.” That’s the point. There is a self unrelated to thinking, an embodied self.

The author related a story from one of the physicians conducting research on advanced Alzheimer’s patients and the self. I personally have experienced the same type of example of the embodied self.

The man said the prayer word for word in Hebrew

While I was a nursing home chaplain a local rabbi invited us to bring our Jewish residents to his synagogue. They had recently received a Torah restored from stolen scrolls hidden by the Nazis during World War II. One of our residents was a man with advanced Alzheimer’s. He could still walk and talk but did not know who he was nor who his wife of 60 years was. The man sat on the front row in the worship room with a yarmulke on his head and a prayer shawl over his shoulders as he had done in his younger non brain-damaged days. This man had not said an intelligible sentence in months if not years.

The rabbi brought the covered Torah to the man and asked him to recite the prayer said before the uncovering of the scroll. The man said the prayer, without hesitation, word for word in Hebrew. His wife next to him wept. I was in tears. A moment of clarity. Had we asked the man to repeat the prayer back at the memory care unit he would not have been able to do it. The synagogue, the rabbi, the yarmulke, the Torah, all connected with the self beyond thinking located in his body.

We all have this self. Only our thinking is so dominant that we do not recognize it. When the thinking recedes we are still there — in our bodies.

Photo by Artem Maltsev on Unsplash