“Should I take my 13-year-old boys to the funeral?” a friend of mine asked. It was a very tragic situation. Her boys were on a soccer team where two of the teammates had already lost their fathers—one to cancer and another in an industrial accident. But this new loss was even worse. Two of the boys on the team were killed by their own father as part of a murder-suicide.

Would this haunt them for years if they got too close?

This mother was concerned about the long-term effects of the boys being exposed to such a horrific loss of life. Would taking them to the wake and funeral make them overly anxious about whether this could happen to their family? Would they have nightmares? Would this haunt them for years if they got too close?

It almost goes without saying, but I assured this mother that she knows her boys better than anyone and she will make the right decision. I repeated my oft-repeated mantra—you can never make a wrong decision. You make the best decision you can with the information you have at the time.

I did say, in general, 13-year-olds should be able to handle the emotions and thoughts that may arise by attending a funeral. Also, in general, I feel it is good for this age children to be exposed to the rituals around death and dying. As much as death is a part of movies, TV, and video games, most of our society does not see death as a normal part of life. Such unfamiliarity makes it so much harder to deal with when it strikes close to home. I went on to say that the horrific nature of these particular deaths may be cause to limit her boys’ exposure. She has to make that call.

In some ways it is actually a good sign that our society does not often see death personally. Many people do not lose their grandparents until they reach adulthood. With rising life expectancy most of those who die are very old. There are exceptions for some segments. The poor may have more health problems that bring early death and some communities experience have higher rates of violent deaths. I would not wish higher death rates on any portion of our citizenry.

How does a nation cope with the enormity of this loss of life?

There was a time when death was all too familiar. Coincidently, this family tragedy happened the same week as the PBS special “Death and the Civil War” aired. From 1861 to 1865 an estimated 750,000 Americans died in the conflict or 2.5 percent of the population. Transpose those figures to our current population and it would be like seven million people died. How does a nation cope with the enormity of this loss of life?

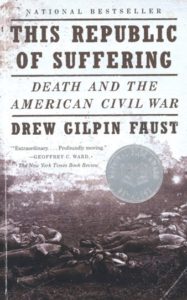

The PBS presentation was based on a book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust. Although Americans, in 1860, would have been familiar with death, the nature and scale of the suffering brought on by the Civil War were unimaginable. We know our ancestors lived close to death. Visit any old cemetery and one is struck with how many young children died. Before the Civil War people often died of a short illness, at home with their family around them. There were last words spoken, prayers, the deceased laid out in the living room, and a funeral service. These practices made up the “good deaths.” But these rituals rarely happened with wartime deaths.

The PBS presentation was based on a book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust. Although Americans, in 1860, would have been familiar with death, the nature and scale of the suffering brought on by the Civil War were unimaginable. We know our ancestors lived close to death. Visit any old cemetery and one is struck with how many young children died. Before the Civil War people often died of a short illness, at home with their family around them. There were last words spoken, prayers, the deceased laid out in the living room, and a funeral service. These practices made up the “good deaths.” But these rituals rarely happened with wartime deaths.

Both sides expected the Civil War to be short and not that painful. The Union army drafted men to serve for only 90 days. There was no ambulance service, no provision for identifying and burying the dead, no system for notifying the next of kin. The soldiers faced a death unlike the “good deaths” they might have witnessed back home. Often killed instantly by a bullet, there was no time for last words. There was no family gathered around. If the soldier’s army had been defeated on the battlefield and fled, there were no comrades to bury them.

Wartime deaths beg for meaning. Why did all these men die? For the North, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address summarized the meaning that these men “shall not have died in vain.” They died to preserve the union and grant freedom to all who dwell in our land. He spoke at the dedication of the first of the National Cemeteries. For the South, finding meaning was more difficult but in the years that followed, the idea of the “lost cause” helped give meaning. Both North and South spent years repatriating remains and establishing cemeteries near sites of battles or prisons.

Death is more distant, remote

And today? Most often the old in poor health are in nursing homes or other facilities and not an active part in the lives of their families. Most people die in institutions like hospitals, although hospice is helping more die at home. Death is more distant, remote. Because sickness, decline and death are often hidden we lose the opportunity for personal and spiritual growth by not contemplating death. The boys on the soccer team can benefit from learning early the harsh realities of life. Hopefully, they will appreciate the gifts of life and of their healthy families. Hide death from them and you hide one of the most profound aspects of life on earth.

Read the words of Michel de Montaigne, c. 1580-1595:

“To begin depriving death of its greatest advantage over us, let us adopt a way clean contrary to that common one; let us deprive death of its strangeness; let us frequent it, let us get used to it; let us have nothing more often in mind than death. At every instant let us evoke it in our imagination under all its aspects….To practice death is to practice freedom. A man who has learned how to die has unlearned how to be a slave. Knowing how to die gives us freedom from subjection and constraint. Life has no evil for him who has thoroughly understood that loss of life is not an evil.”

Photo by Jesús Rodríguez on Unsplash