“Chaplain Dunn, we need you in the emergency room,” the nurse started her call to me on a Saturday morning. “An eight-day-old baby died at his mother’s breast at home and the family needs your support.” This family had no minister to call. I did what I could for them. It was a sad, sad situation. A few hours later the funeral home called, and the family asked if I could conduct a graveside service for the child.

For twenty years, for one week each quarter, I volunteered as the on-call chaplain at the Loudoun Hospital Center in Virginia. During normal business hours, there was a full-time chaplain ready to handle emergencies. I almost always got a few calls each week I was on duty. Often, it was for deaths in the ER. Sometimes, it was for stillbirths or neonatal deaths. The staff knew they needed to provide spiritual support in times of crisis. Who could they call after hours?

The mysterious absence of chaplains

As I wrote in my last blog, we have been binge-watching Grey’s Anatomy during the pandemic. In the over 300 episodes of Grey’s Anatomy I have watched, I can’t recall a time when a chaplain was on camera. Isn’t that curious? Like all medical dramas, the show is filled with crises and death. Where are the chaplains? Full disclosure here: I am a chaplain and could be protecting my turf.

One past TV medical drama, M*A*S*H (1972-83), cast a chaplain in a significant role. The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital amid the Korean War might make the presence of a chaplain seem more acceptable. After all, it was the Army in the middle of a war. The chaplain, Father Mulcahy (a Catholic priest), was one of only four characters who appeared in all eleven seasons of the hit show — along with “Hawkeye,” “Hot Lips” Houlihan, and the crossdressing Klinger.

There was one Grey’s episode when two doctors talked about needing to get a chaplain. A patient was asking for forgiveness. He was the landlord of an apartment building that had collapsed resulting in multiple injuries and some deaths. He said he was trying to save up the money to make repairs to the structural damage the building had suffered in an earthquake. Now, people had died because of his procrastination and he wanted to be forgiven.

Dr. Ben Warren said, “The chaplain is M.I.A. and I heard there was a rabbi in geriatrics.”

Dr. Leah Murphy encouraged Ben to go see the patient and act as chaplain, “All you have to do is listen and nod your head.”

Dr. Warren did see the patient and told him he was not a priest. The guilt-ridden landlord said, “I just need someone to listen.”

The spiritual side of Grey’s Anatomy

Just because the show is absent chaplains or other clergy does not mean it does not tackle some very important spiritual and religious topics. More than once did a child need life-saving medical treatment when one parent wanted to trust the doctors and the other wanted to take the child home and trust God only. Similarly, a Jehovah’s Witness patient refused to accept a blood transfusion that could have saved his life but would violate his strongly held religious belief. A new intern felt compelled to use her hijab to stop the bleeding in a patient. It was later was returned to her, cleaned, by a fellow physician who knew the spiritual importance of the head covering.

Rabbi Eli, a dying patient, comforts Dr. April Kepner

For nine seasons of Grey’s most of the “spiritual teaching,” centers around the character, Dr. April Kepner. She starts out on the show as a conservative Christian and something of a prude. Gradually, life seems to interrupt her strongly held beliefs and morals. She loses her virginity and then recommits to a chaste life in an effort to “re-virginize.” She gets married, has a child die soon after birth, gets a divorce, and has another child as a single mother. Her own painful life story and the random tragic stories of her patients causes a crisis of faith in Dr. Kepner.

The journey we’re all on

Kepner’s breakthrough to a more mature faith is helped by a dying patient, Rabbi Eli. He is dying because of a mistake made by Dr. Miranda Bailey. Kepner views Eli’s case as just more evidence that God does not care for us. She wants a guarantee that if you are faithful good things will come your way.

The rabbi will have none of the guarantee talk. He recites a long list of faithful biblical characters who were tragic victims. Eli says it’s also in “the sequel” (by which he means the New Testament). He argues that if only good things happened in these stories, the bible would not have been a best-seller.

Rabbi Eli helps Dr. Kepner through her crisis of faith

“Who are you to know why some people live and some people die?” the dying man tells Dr. Kepner. “God’s not indifferent to our pain…the world is full of brokenness and it’s our job to put it back together again.” He asks her to tell Dr. Bailey he forgives her for her mistake. He dies confusing Dr. Kepner with his wife who is out of town. Get out the tissues.

Occasionally, the hectic scenes in Grey’s O.R. and E.R. shift to the quiet of the chapel. Doctors pray, light candles, or just sit silently. Here, Kepner walks in on a distraught Dr. Bailey who is lighting a candle and seeking solace.

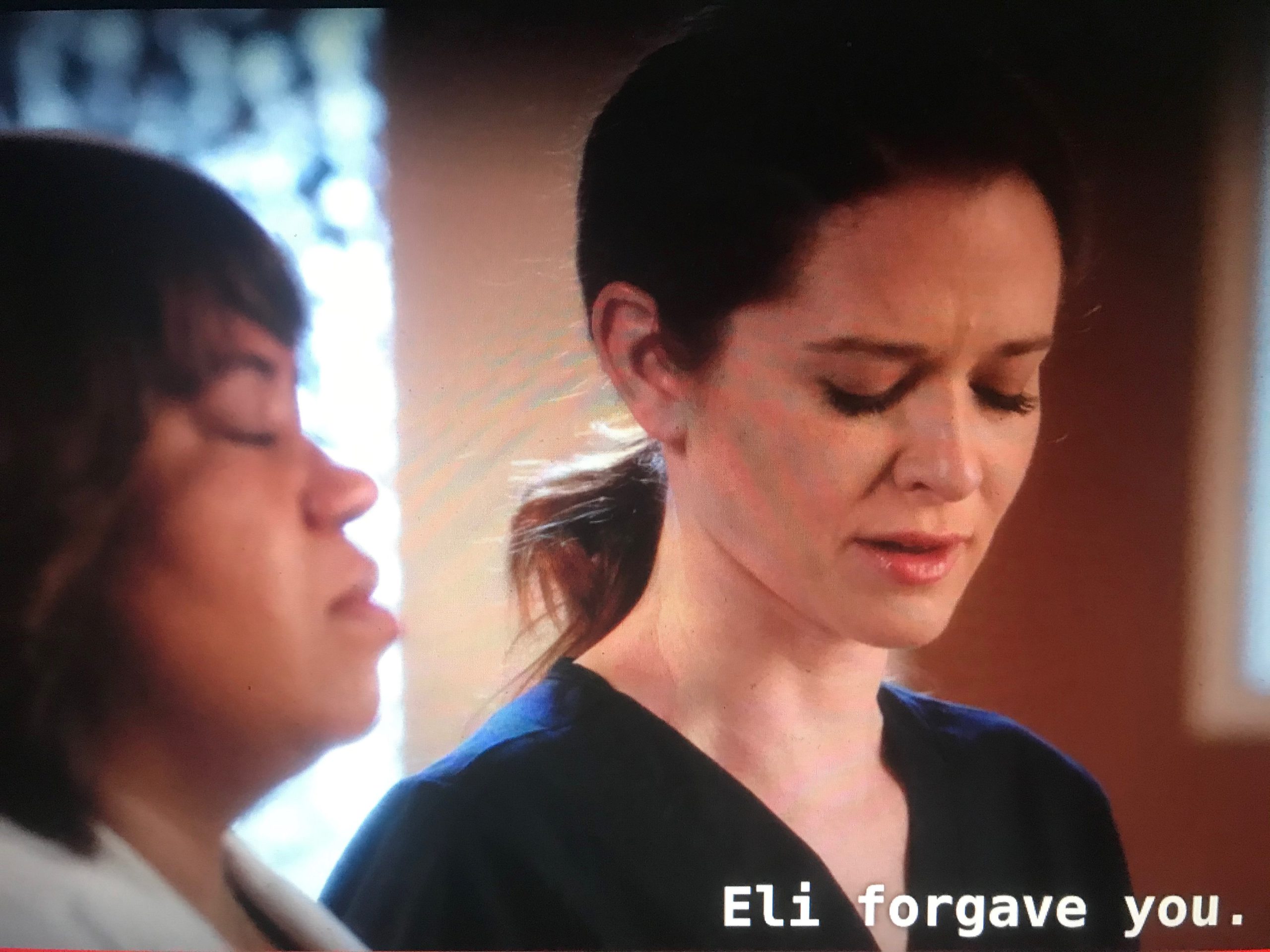

Dr. Kepner comforts Dr. Bailey, who made the medical mistake that led to Rabbi Eli’s death

Dr. Kepner tells her, “Eli forgave you. Some things just happen, and we don’t get to know why.” She came to a point of acceptance and was able to comfort a fellow traveler in this seemingly unfair world. Is this not the journey we are all on?