A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be?

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be?

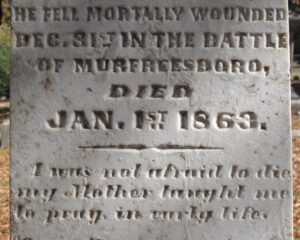

Barringer’s marker caught my eye as I wandered around St. Peter’s Cemetery in Oxford, Mississippi. The epitaph, “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life,” got me thinking about what it means to have a good death. (See my “Hank’s Deep Thoughts” video at the monument.)

Let me clarify; a “good death” does not mean that it was good that William died. Death to the young is, of course, a tragedy. And, as a POW, he likely did not die in ideal conditions.

Being a prisoner of war was not mentioned on the monument. I did an internet search and found him on a list of soldiers who died in captivity, hundreds of miles away in Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

A “good death” through the centuries

Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride.

Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride.

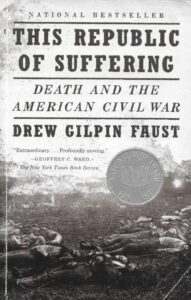

By the American Civil War (1861-65), the dying and their families knew what was expected. Drew Gilpin Faust identified four elements of a good death in her moving book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and The American Civil War. According to Faust, a good death in the 19th century was one where the dying person:

Was conscious

Was conscious- Was not afraid of dying

- Was prepared spiritually to meet their maker

- Left dying words for the family

Even the atheist Charles Darwin, who died in 1882 in England, kept to this script. He told his wife on his deathbed, “I am not the least afraid of death—Remember what a good wife you have been to me—Tell all my children to remember how good they have been to me.”

Though a reference to spiritual things was conspicuously absent, Darwin was conscious, was not afraid of dying, and left last words for his family. In my interpretation, he wanted to emphasize that even though he had no spiritual leanings, he was still “not the least afraid of death.”

Much has changed since the Civil War, including our expectations about our deaths. Today, medical literaturedescribes what many now consider a good death: being in control, being comfortable and free of pain, having a sense of closure, etc.

This sense of control has recently manifested itself through eleven U.S. jurisdictions adopting medical aid in dying. In those places, patients can ask a physician to give them medication to hasten their dying.

Back to Mr. Barringer

The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

And there it is. William was conscious, he was not afraid of dying, he was prepared spiritually (thanks to his mother), and these are the words he left for others. I can imagine his mother visiting this monument often in her grief and being consoled, “At least he had a good death.”

__________________________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.