I often think about spending my last years of life in memory loss.

Hank’s extended family of origin, 1960. All but one of the adults in this photo died with dementia

One photo says it all. 1960. I am twelve. My mother’s family of origin gathered with our various aunts, uncles, and cousins surrounding my grandmother. Seven adults and seven children. Six of the seven adults died with dementia. Aunt Martha was the only one spared, and she was not a blood relative of mine.

My mother, who probably had Alzheimer’s, died at age 92. Dad got a double-whammy of Parkinson’s and multi-infarct dementia (a series of small strokes). He was 85 at death. Both spent their final years in a nursing home or a memory care unit.

What I can control

Hank with his mother at her memory care unit.

There are no cures for the various forms of dementia that could befall me. Yet, there are actions I can take to reduce the risk or delay the onset of cognitive impairment.

I have written before about reducing the risk of dementia and how my hearing loss is a risk factor that could lead to cognitive decline.

Recently, I read an article in JAMA titled “Lifestyle Enrichment in Later Life and Its Association With Dementia Risk.” Here is part of the summary of the research:

“[M]ore frequent engagement in adult literacy activities (e.g., writing letters or journaling, using a computer, and taking education classes) and in active mental activities (e.g., playing games, cards, or chess and doing crosswords or puzzles) was associated with an 11.0%… and a 9.0%… lower risk of dementia, respectively.”

Author event with Ann Patchett at Square Books, Oxford, Miss.

Keeping my mind active

I read articles like this recent one and wonder, “Am I reducing my risk?” I like to say, “Yes, I am.”

Looking back at my previous blogs about reducing the risk of memory loss, I can check several boxes. I work at vigorous physical activity and try to get enough sleep. Several times a week, I journal and often am on my computer (maybe too often?). Almost weekly, I attend an author event at Square Books or a lecture at the university’s Overby Center for Southern Journalism and Politics or at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture.

All the advice includes staying engaged socially to keep the mind active. Besides church activities, I attend two weekly men’s groups. One is here in Oxford, where we sit around and mostly talk about politics. The other is on Zoom with the group I have been in since 1992.

I like to think I would be doing all this active-mind stuff even if there were no evidence of health benefits. I just enjoy all the activities I mentioned above.

Even my father’s active mind suffered cognitive decline

Hank with his nursing home resident father

All the advice is about REDUCING the risk of dementia, not PREVENTING it. A good case in point is my father. He was a lifelong reader and writer. He authored almost a score of books. Even while in the nursing home, he tried to write a weekly column for publication.

Mom told me that as it became more difficult for Dad to compose a few paragraphs, she suggested they stop making the effort. Dad responded like a typical child of the Depression, “We need the money.” They didn’t need the money, and he eventually gave up on writing.

Even though Dad kept an active mind, he did not “check all the boxes.” He never participated in vigorous physical activity and was a heavy smoker for probably thirty years.

There are enough examples of public figures who ended their days with cognitive impairment, like Ronald Reagan and Pat Summitt. The mental exertion necessary to be President for eight years or to win eight national basketball championships did not prevent memory loss in the end.

My preparing for the worst

Knowing that memory loss could likely be in my future, I have made a few preparations. Like my parents, I have purchased long-term care insurance. They both used every bit of the four years of benefit that paid for their institutional care.

I also recently added an addendum to my living will, instructing my family to withhold hand-feeding if I reach stage 6 or 7 on the Functional Assessment Staging Tool. I have used the addendum put out by End of Life Choices, New York, which is in line with my right to refuse medical treatment. I discussed this Voluntary Stopping Eating and Drinking (VSED) in a previous blog.

Whew! That’s a lot. I think I’ll take a nap — also one of the boxes to check.

________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together, they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

To qualify for hospice under the Medicare benefit, a physician has to say, “This patient has, at most, six months to live if the disease runs its normal course.” What happens if the prognosis is wrong and the patient is still alive after six months?

To qualify for hospice under the Medicare benefit, a physician has to say, “This patient has, at most, six months to live if the disease runs its normal course.” What happens if the prognosis is wrong and the patient is still alive after six months?

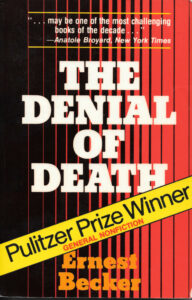

Two months after he died, Ernest Becker won the 1974 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction for his book The Denial of Death. I guess, since he was dead, he was not a winner, but his book was.

Two months after he died, Ernest Becker won the 1974 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction for his book The Denial of Death. I guess, since he was dead, he was not a winner, but his book was. I’ll get to Becker’s deathbed below but first a few quotes from his classic. Note that Becker wrote in 1973 just as we were becoming aware that we no longer refer to all humans as “man.” I know better now but I will let his original words stand.

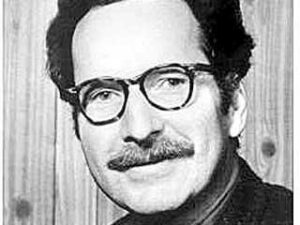

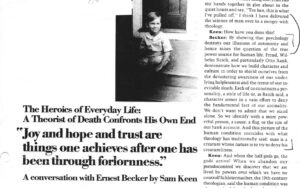

I’ll get to Becker’s deathbed below but first a few quotes from his classic. Note that Becker wrote in 1973 just as we were becoming aware that we no longer refer to all humans as “man.” I know better now but I will let his original words stand. Soon after The Denial of Death arrived in late 1973, Sam Keen, one of the editors at the prestigious Psychology Today magazine, called Becker’s home hoping to set up an interview. Keen explained how the deathbed interview came about: “I called his home in Vancouver to see if he would be willing to tape a conversation. His wife Marie informed me that he had just been taken to the hospital and was in the terminal stage of cancer. The next day she called to say that Ernest would very much like to do the conversation if I could get there while he still had strength and clarity. So I went to Vancouver with speed and trembling, knowing that the only thing more presumptuous than intruding into the private world of the dying would be to refuse the invitation.”

Soon after The Denial of Death arrived in late 1973, Sam Keen, one of the editors at the prestigious Psychology Today magazine, called Becker’s home hoping to set up an interview. Keen explained how the deathbed interview came about: “I called his home in Vancouver to see if he would be willing to tape a conversation. His wife Marie informed me that he had just been taken to the hospital and was in the terminal stage of cancer. The next day she called to say that Ernest would very much like to do the conversation if I could get there while he still had strength and clarity. So I went to Vancouver with speed and trembling, knowing that the only thing more presumptuous than intruding into the private world of the dying would be to refuse the invitation.” When I first walked into the home, I sat alone with the wife in the living room. She was very comfortable talking about her husband’s impending death. I asked her, “What is all this about not wearing our pins or talking about death? Does your husband know he is dying?” She said, “Oh, yes, he knows he is dying.” I asked, “How do you know he knows?” She responded, “Because he asked me.” I asked how she responded to him and she had told him, “Not while I’m around.”

When I first walked into the home, I sat alone with the wife in the living room. She was very comfortable talking about her husband’s impending death. I asked her, “What is all this about not wearing our pins or talking about death? Does your husband know he is dying?” She said, “Oh, yes, he knows he is dying.” I asked, “How do you know he knows?” She responded, “Because he asked me.” I asked how she responded to him and she had told him, “Not while I’m around.”

I read a recent JAMA Online article titled “

I read a recent JAMA Online article titled “ Changing “What does the patient WANT?” to “What does the patient THINK…”

Changing “What does the patient WANT?” to “What does the patient THINK…” Soon after I became a part-time nursing home chaplain in 1983, our administration formed an ethics committee. Virginia had just passed a “Natural Death Act,” which gave patients a right in the code to refuse treatment and provided a form (e.g., “living will”) to express their treatment preferences.

Soon after I became a part-time nursing home chaplain in 1983, our administration formed an ethics committee. Virginia had just passed a “Natural Death Act,” which gave patients a right in the code to refuse treatment and provided a form (e.g., “living will”) to express their treatment preferences.