The old man had come to our nursing home from the hospital in declining health with late-stage dementia. Almost immediately upon arrival, he had a medical crisis. Because he was a “full code” (everything should be done to save his life in a medical emergency), the nursing staff called 911, and he was off to the hospital again. I rode with him in the ambulance.

While waiting for the daughter’s arrival, the ER doc asked me, “What is his code status?” I told him.

While waiting for the daughter’s arrival, the ER doc asked me, “What is his code status?” I told him.

Part of my role as the nursing home chaplain was to talk to all new patients and/or their families about advance directives and the possibility of a “No CPR” order. This resident was so new to us that I had no time to contact the daughter, the decision-maker in this case.

Explaining the need for a “No CPR” order

Photo by Kier in Sight Archives on Unsplash

The daughter arrived at the ER and went directly to her father’s side. He was responsive and not actively dying (though he would indeed die within a week). With her permission, I offered a prayer. I then asked her to come into the hallway so we could talk.

She was still dressed in business attire, having rushed over from a corporate or government office in the D.C. metro area. She seemed well-informed, intelligent, caring and involved. An ideal audience for my “No CPR” discussion.

I explained CPR and its lack of success in saving patients in her father’s condition. She seemed to understand and said she wanted her dad to be comfortable, knowing the end was near. I told her she would need to request a “No CPR” order from the physician.

Surprise indecision

Photo by SHVETS production

A few days later, the man returned to the nursing home. To my surprise, he was still a “full code.” I thought, “Didn’t she listen to me? She seemed to want comfort only and no CPR.” I called her and went through my standard spiel about the lack of benefits of CPR.

The daughter stopped me mid-spiel. She said, “I know CPR will not save my father’s life. I want him to die peacefully. But it is just so hard letting go.”

I wrote her off as “ambivalent.” I didn’t think she could make up her mind. Turns out, it was the emotional act of calling the doctor to request a “No CPR” order that symbolized her holding on — not letting go. She was trapped in ambivalence; she didn’t want her father to die…but she wanted him to have a peaceful death.

Frustration with ambivalent patients/families among providers

This story about this patient and his daughter came to mind as I listened to a recent GeriPal podcast, “Ambivalence in Decision-Making.” The two physician hosts discuss the topic with three bioethicists and a doctor. You can listen to the podcast, watch it on YouTube, or read a transcript. Dr. Josh Briscoe discusses this thoroughly in a substack post, “Ambivalence in Clinical Decision-Making: Or, Having Your Cake and Eating it Too.”

This story about this patient and his daughter came to mind as I listened to a recent GeriPal podcast, “Ambivalence in Decision-Making.” The two physician hosts discuss the topic with three bioethicists and a doctor. You can listen to the podcast, watch it on YouTube, or read a transcript. Dr. Josh Briscoe discusses this thoroughly in a substack post, “Ambivalence in Clinical Decision-Making: Or, Having Your Cake and Eating it Too.”

Healthcare providers — doctors, nurses, social workers, and chaplains — see this all the time. We can feel frustrated that people can’t make up their minds. Did I not explain it well enough? Do they need more information?

One of the guests on the podcast note, “Ambivalence should be a flag that something’s going on here, something’s important, and we should slow down and pay attention to that.”

They then go on to reframe this indecision as a good thing, saying that ambivalent decision makers “are really sitting with their options and sitting in that tension. And that for us, felt almost like [it was] a good thing. Look how seriously someone’s taking this decision, right? They really want to make sure they get it right and that it’s a choice they can live with.”

At the end of my story, the daughter did request the “No CPR” order. Her dad died a few days later, peacefully.

_____________________

Author Chaplain Hank Dunn, MDiv, has sold over 4 million copies of his books Hard Choices for Loving People and Light in the Shadows (also available on Amazon).

I read a recent JAMA Online article titled “

I read a recent JAMA Online article titled “ Changing “What does the patient WANT?” to “What does the patient THINK…”

Changing “What does the patient WANT?” to “What does the patient THINK…” Soon after I became a part-time nursing home chaplain in 1983, our administration formed an ethics committee. Virginia had just passed a “Natural Death Act,” which gave patients a right in the code to refuse treatment and provided a form (e.g., “living will”) to express their treatment preferences.

Soon after I became a part-time nursing home chaplain in 1983, our administration formed an ethics committee. Virginia had just passed a “Natural Death Act,” which gave patients a right in the code to refuse treatment and provided a form (e.g., “living will”) to express their treatment preferences.

The patient had left verbal and written instructions that she did not want to have life-saving treatments when she was dying. A “No CPR” order was on her chart. Knowing her daughter’s feelings, the old lady chose her son as her power of attorney. She conspicuously omitted any mention of her daughter in the document.

The patient had left verbal and written instructions that she did not want to have life-saving treatments when she was dying. A “No CPR” order was on her chart. Knowing her daughter’s feelings, the old lady chose her son as her power of attorney. She conspicuously omitted any mention of her daughter in the document.

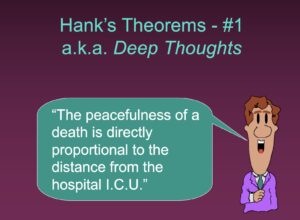

About that same time, I started traveling around the country making presentations to healthcare professionals. My most popular talk, “Helping Patients and Families with End-of-Life Decisions,” includes a series of slides with “Hank’s Theorems” on various end-of-life issues. The first slide says, “The peacefulness of a death is directly proportional to the distance from the hospital ICU.”

About that same time, I started traveling around the country making presentations to healthcare professionals. My most popular talk, “Helping Patients and Families with End-of-Life Decisions,” includes a series of slides with “Hank’s Theorems” on various end-of-life issues. The first slide says, “The peacefulness of a death is directly proportional to the distance from the hospital ICU.”