“I pray for peace,” said the man with advanced cancer. He was a new in-home hospice patient I was visiting for the first time. Turns out, I knew his wife as a coworker at the nursing home from years before — she was a nurse, and I was the chaplain.

We were sitting in the upstairs bedroom of their suburban home. He was in a wheelchair, and I was sitting in front of him. His wife was in a chair on the other side of the room. I often ask patients, “Do you pray?” And like most everyone else, this man replied, “Yes.”

We were sitting in the upstairs bedroom of their suburban home. He was in a wheelchair, and I was sitting in front of him. His wife was in a chair on the other side of the room. I often ask patients, “Do you pray?” And like most everyone else, this man replied, “Yes.”

“What do you pray for?” was, of course, my next question. “I pray for peace,” he immediately responded. Across the room, out of sight of my patient, his wife was shaking her head, as if to say, “That’s not what I pray for.”

As we walked down the stairs on my way out, she confided, “I pray for a cure.” That was totally understandable.

This scene came to mind as I listened to a recent GeriPal Podcast titled, “What Makes a Good Death?” I have also explored this topic in a previous blog, “Can a POW Have a Good Death Hundreds of Miles from Home.”

Peace is more important to patients than doctors imagine

Photo by Raphael Nogueira on Unsplash

The “GeriPal” podcast focuses on geriatrics and palliative care. Each week, they feature the latest research on a variety of topics. Last week, they were revisiting the idea of a good death from the perspectives of patients, families, doctors, and other healthcare professionals. They also discussed a new paper comparing and contrasting the idea of a good death as found in Brazil versus the United Kingdom.

One of the surprises in the research is that although patients felt being at peace was important, physicians did not believe that it was that important for a “good death.” Another curious finding was that doctors rated being pain-free higher than patients did. Perhaps that was related to the finding that patients rated being mentally aware as more important and doctors not so much.

Control in Brazil v. the UK

Photo by Marcin Nowak on Unsplash

Another interesting finding was the idea of being in control of the dying process. Folks in the United Kingdom ranked being in control as very important. Responses from Brazil were essentially, “What do you mean by ‘control?’ God is in control.” This, of course, reflects the more religious leanings in Brazil compared to the more secular UK.

The bottom line — listen to patients

Researchers concluded by warning all of us not to make assumptions about a particular patient or their family. Yes, there are often common ideas about what constitutes a “good death.” But this particular patient might not agree. So, we need to stay curious — and ask.

The whole podcast episode is worth a listen or, at least, read the transcript.

__________________

Author Chaplain Hank Dunn, MDiv, has sold over 4 million copies of his books Hard Choices for Loving People and Light in the Shadows (also available on Amazon).

Recently,

Recently,  Then, of course, “happy” is

Then, of course, “happy” is  Recently, I

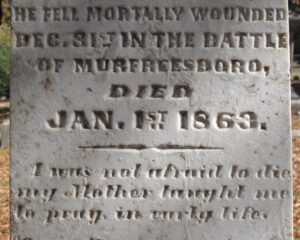

Recently, I  A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be?

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be? Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride.

Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride. Was conscious

Was conscious