My wife does not like tomatoes, but I married her anyway. She can’t help herself. I don’t recall that our preference for or against tomatoes came up when we were dating. Does anyone think of such things to ask a potential life partner? I think not.

I recently posted a video of me eating a tomato sandwich, just bread, mayonnaise, and thick, juicy, farm-fresh tomatoes. I closed the reel commenting that there is no free will in whether we like tomatoes, “Perhaps there are more things we think we are making choices about, but we really aren’t.”

I recently posted a video of me eating a tomato sandwich, just bread, mayonnaise, and thick, juicy, farm-fresh tomatoes. I closed the reel commenting that there is no free will in whether we like tomatoes, “Perhaps there are more things we think we are making choices about, but we really aren’t.”

NOT ONE of the many comments on the post picked up on the lack of free will. Everyone wanted to talk about their love of tomatoes and all the different ways to eat them. Our love (or dislike) of tomatoes is an easy example of how we lack free will.

A lot goes into acquiring a taste for a food: where you grew up, what your family ate in your childhood, textures you like or dislike, or how a particular food settles in your stomach. You don’t “choose” to like a tomato, you either do or don’t based on many factors outside of your control.

A lot goes into acquiring a taste for a food: where you grew up, what your family ate in your childhood, textures you like or dislike, or how a particular food settles in your stomach. You don’t “choose” to like a tomato, you either do or don’t based on many factors outside of your control.

Judgement or pride have no place when you accept that there is no free will in a liking for tomatoes. There is no judgement by us tomato lovers toward those who dislike them. Heck, more are available for me if a certain portion of the population dislikes them. Conversely, there is no sense of pride or achievement by those of us who have attained such a refined palate to appreciate a fine tomato. We are just the lucky ones.

Free will and “choice” in end-of-life decisions

I have made a career of helping patients and families with end-of-life decisions as a healthcare chaplain and author of Hard Choices for Loving People, which has sold over 4 million copies. The first chapter on CPR discusses the “choice” a caregiver may need to make to put a frail or elderly patient through a resuscitation attempt.

I have made a career of helping patients and families with end-of-life decisions as a healthcare chaplain and author of Hard Choices for Loving People, which has sold over 4 million copies. The first chapter on CPR discusses the “choice” a caregiver may need to make to put a frail or elderly patient through a resuscitation attempt.

I remember the scores of patients and families I helped make end-of-life decisions as a nursing home chaplain. Most often, once I explained that only about 1% of nursing home patients survive the event that led to CPR and survivors are in much worse shape than before, the families would say, “No CPR. Let her go in peace.”

But occasionally, they would say, “Life is precious no matter how poor, and a 1% chance IS a chance. We love grandma and don’t want her to die,” and then the patient remained a full code.

Did these families exercise their free will in making these choices? What if the “choice” was not consciously made by the caregiver but resulted from a series of factors and information leading up to the decision?

Determined: A Science of Life without Free Will

Last year, Robert M. Sapolsky started making the media rounds, including a New York Times interview and a guest appearance on Sam Harris’ Making Sense podcast. He has a new book, Determined: A Science of Life without Free Will. Yes, THAT free will.

Last year, Robert M. Sapolsky started making the media rounds, including a New York Times interview and a guest appearance on Sam Harris’ Making Sense podcast. He has a new book, Determined: A Science of Life without Free Will. Yes, THAT free will.

Sapolsky presents a credible argument that we are not making “choices” the way we think we are, based on the science of our brains. Here’s an excerpt of his argument:

“Once you work with the notion that every aspect of behavior has deterministic, prior causes, you observe a behavior and can answer why it occurred: because of the action of neurons in this or that part of your brain in the preceding second. And in the seconds to minutes before, those neurons were activated by a thought, a memory, an emotion, or sensory stimuli.…We are nothing more or less than the cumulative biological and environmental luck, over which we had no control, that has brought us to any moment.”*(see his full 4-paragraph summary below)

What about that family who “chose” a full code for their frail, failing, nursing home patient? Maybe they watched Rescue 911 on TV, where 100% of patients getting CPR survived (see my previous blog about CPR on TV). Perhaps this previous exposure to all of the CPR successes on TV makes them say, “Yes, do everything,” without even thinking about it.

What about that family who “chose” a full code for their frail, failing, nursing home patient? Maybe they watched Rescue 911 on TV, where 100% of patients getting CPR survived (see my previous blog about CPR on TV). Perhaps this previous exposure to all of the CPR successes on TV makes them say, “Yes, do everything,” without even thinking about it.

Why present a choice if there is no free will?

So why would I take the time to explain CPR and present a “choice” to use it or not, if there is no free will to make that choice? Maybe they did not know about the 1% survival rate. This new information might connect to millions of bits of data previously registered in the family’s brains, activating an assessment that Grandma would likely not survive.

I’d also have these conversations because I can’t help myself. I am compelled by forces within my brain, formed over years of experience, for which I have no control: Talking about end-of-life decisions was part of my job, family values instilled in me from my youth was to do your duty on the job, the long line of nurses in my family fostered a natural compassion for these patients and families.

I believe the scientific evidence Sapolsky presents that we have no free will is quite compelling. Most people may disagree, citing religious and spiritual arguments over whether or not we have free will.

Humor me on this one. If there is no free will, we must be less judgmental of those who “choose” a path we feel is wrong. If they’re basing that decision on information spanning generations, they couldn’t help themselves. Conversely, I can’t take credit if my actions led to more compassionate end-of-life care for a patient. I had nothing to do with all that went into their family’s “choices.”

In this brief blog, I cannot begin to cover what it took Sapolsky over 500 pages to say, but I added a larger excerpt of his book below.

Now I’ve got to go back to the farmer’s market because I am out of tomatoes. I can’t help myself.

__________________

Author Chaplain Hank Dunn, MDiv, has sold over 4 million copies of his books Hard Choices for Loving People and Light in the Shadows (also available on Amazon).

Follow Hank: LinkedIn | Instagram | Facebook | YouTube

_________________________________________

*Below is the summary of the basic thesis by Robert M. Sapolsky in his book, Determined: A Science of Life without Free Will, pages 3-4

“Once you work with the notion that every aspect of behavior has deterministic, prior causes, you observe a behavior and can answer why it occurred: as just noted, because of the action of neurons in this or that part of your brain in the preceding second. And in the seconds to minutes before, those neurons were activated by a thought, a memory, an emotion, or sensory stimuli. And in the hours to days before that behavior occurred, the hormones in your circulation shaped those thoughts, memories, and emotions and altered how sensitive your brain was to particular environmental stimuli. And in the preceding months to years, experience and environment changed how those neurons function, causing some to sprout new connections and become more excitable, and causing the opposite in others.

“And from there, we hurtle back decades in identifying antecedent causes. Explaining why that behavior occurred requires recognizing how during your adolescence a key brain region was still being constructed, shaped by socialization and acculturation. Further back, there’s childhood experience shaping the construction of your brain, with the same then applying to your fetal environment. Moving further back, we have to factor in the genes you inherited and their effects on behavior.

“But we’re not done yet. That’s because everything in your childhood, starting with how you were mothered within minutes of birth, was influenced by culture, which means as well by the centuries of ecological factors that influenced what kind of culture your ancestors invented, and by the evolutionary pressures that molded the species you belong to. Why did that behavior occur? Because of biological and environmental interactions, all the way down?

“As a central point of this book, those are all variables that you had little or no control over. You cannot decide all the sensory stimuli in your environment, your hormone levels this morning, whether something traumatic happened to you in the past, the socioeconomic status of your parents, your fetal environment, your genes, whether your ancestors were farmers or herders. Let me state this most broadly, probably at this point too broadly for most readers: we are nothing more or less than the cumulative biological and environmental luck, over which we had no control, that has brought us to any moment.”

While waiting for the daughter’s arrival, the ER doc asked me, “What is his code status?” I told him.

While waiting for the daughter’s arrival, the ER doc asked me, “What is his code status?” I told him.

This story about this patient and his daughter came to mind as I listened to a recent GeriPal podcast,

This story about this patient and his daughter came to mind as I listened to a recent GeriPal podcast,

I read a recent JAMA Online article titled “

I read a recent JAMA Online article titled “ Changing “What does the patient WANT?” to “What does the patient THINK…”

Changing “What does the patient WANT?” to “What does the patient THINK…” Soon after I became a part-time nursing home chaplain in 1983, our administration formed an ethics committee. Virginia had just passed a “Natural Death Act,” which gave patients a right in the code to refuse treatment and provided a form (e.g., “living will”) to express their treatment preferences.

Soon after I became a part-time nursing home chaplain in 1983, our administration formed an ethics committee. Virginia had just passed a “Natural Death Act,” which gave patients a right in the code to refuse treatment and provided a form (e.g., “living will”) to express their treatment preferences.

The patient had left verbal and written instructions that she did not want to have life-saving treatments when she was dying. A “No CPR” order was on her chart. Knowing her daughter’s feelings, the old lady chose her son as her power of attorney. She conspicuously omitted any mention of her daughter in the document.

The patient had left verbal and written instructions that she did not want to have life-saving treatments when she was dying. A “No CPR” order was on her chart. Knowing her daughter’s feelings, the old lady chose her son as her power of attorney. She conspicuously omitted any mention of her daughter in the document.

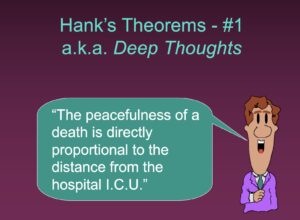

About that same time, I started traveling around the country making presentations to healthcare professionals. My most popular talk, “Helping Patients and Families with End-of-Life Decisions,” includes a series of slides with “Hank’s Theorems” on various end-of-life issues. The first slide says, “The peacefulness of a death is directly proportional to the distance from the hospital ICU.”

About that same time, I started traveling around the country making presentations to healthcare professionals. My most popular talk, “Helping Patients and Families with End-of-Life Decisions,” includes a series of slides with “Hank’s Theorems” on various end-of-life issues. The first slide says, “The peacefulness of a death is directly proportional to the distance from the hospital ICU.”