Why not?

Why wouldn’t you want to know your prognosis if you had an aggressive disease? Wouldn’t it help in choosing treatment options and planning for the future?

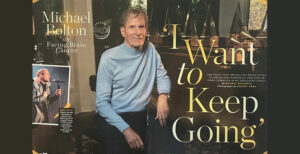

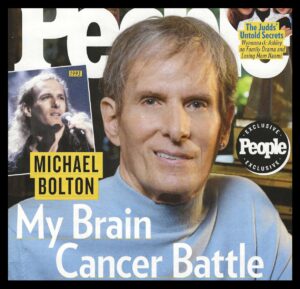

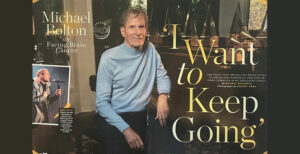

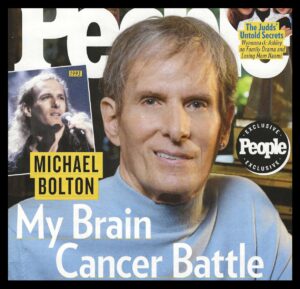

These questions came to mind as I read recent stories about 72-year-old pop singer Michael Bolton’s life with a glioblastoma. Although this type of brain cancer is often fatal, Bolton has told his physicians that he does NOT want to know his prognosis.

From a recent article in People magazine:

From a recent article in People magazine:

“Today Bolton is in what his doctors call a ‘survivorship stage.’ He has purposely not been given a prognosis—and his family is choosing to remain hopeful in the face of daunting statistics. The five-year survival rate for glioblastoma patients is just 6.9 percent, and the average length of survival is eight months, per the Glioblastoma Foundation. Still, ‘our doctor told us that he has patients with glio that he has had for 10 years.’ [Bolton’s daughter] Holly says, ‘In my mind that’s my dad.’”

Could this be DENIAL?

In some cases, not wanting to know a prognosis (or flat-out refusing to accept a fatal diagnosis) could be a form of denial.

Once, on my first meeting with a new hospice patient with metastatic cancer, the husband told me, “God has told me my wife is not going to die, so I don’t want any talk about ‘death’ or ‘dying.’ Only positive thoughts.”

I said to him, “I will honor that, but I do have two concerns. I have had some families say to me, ‘We are hopeful and don’t want any opioids because we are afraid of addiction and hastening death.’ So, one concern is about adequate pain control. The other concern is that if you don’t allow death as a possibility you may miss some very important conversations.”

Both the patient and her husband assured me that she would get whatever pain medications she needed and that they have talked about those important things. I believed them on both counts.

Both the patient and her husband assured me that she would get whatever pain medications she needed and that they have talked about those important things. I believed them on both counts.

Initially, I had the same concerns reading this story. There is no indication that Bolton is not getting the pain meds he may need. But, in choosing not to know his prognosis, is he living in denial of the gravity of his situation? Reading further, I think not.

Bolton said, “It’s a reality of mortality. Suddenly, a new light has gone on that raises questions, including ‘Am I doing the best that I can do with my time?’” This sounds like a man getting ready to die while enjoying what time he might have left (but also not wanting to talk about the amount of time he has left).

The difficulty of making “how-much-time” predictions

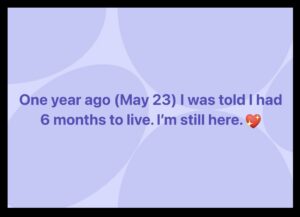

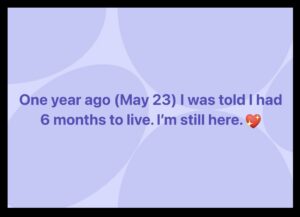

I can understand that a person may not want to know their prognosis because predicting how much time a patient has is so difficult. A Facebook friend recently posted, “One year ago (May 23), I was told I had 6 months to live. I’m still here.”

I can understand that a person may not want to know their prognosis because predicting how much time a patient has is so difficult. A Facebook friend recently posted, “One year ago (May 23), I was told I had 6 months to live. I’m still here.”

My “real” friend, Tom, was diagnosed with stage 3 esophageal cancer in 2009. He was 51. He did want to know his prognosis and was told the 5-year survival rate was 15-20%. He called me at the time and asked if I would be a pallbearer. “Of course,” I said. He’s still here.

On the other side of this are the patients who enroll in hospice and die just days after admission. Sometimes, the problem is that the doctor waits until the last minute to tell patients the truth, “You are dying.” Then, some patients and families have been told the truth but want to be hopeful and choose not to go on hospice.

Physicians are now encouraged to ask themselves the “surprise question:” Would you be surprised if you heard that this patient had died in the next six months? If the answer is “No. I would not be surprised,” then it is time to make that hospice referral.

@hospicenursepenny’s thoughts on the importance of talking about it

@hospicenursepenny’s thoughts on the importance of talking about it

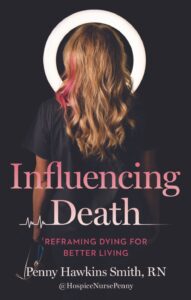

Penny Hawking Smith, R.N. has a great chapter on this topic, “The Need to Know,” in her book Influencing Death. This is what she has to say about getting the “bad news” out there:

“Truthfully, a dying person’s prognosis is often the elephant in the room.… Families don’t want to bring it up to the dying person because there’s a common fear it will take away their person’s hope, making them die faster; I’m here to call bull**** on that. On the other hand, the dying person sometimes doesn’t want to bring it up to their family and bum them out, which, of course, it will. My advice? You’re dying, so they’re going to be bummed either way. At least getting the subject on the table will allow for meaningful conversations that might not happen otherwise.”

Having “hope” while preparing to die

Michael Bolton may indeed have a prognosis longer than six months. I wish this for him and his family. They say they want to remain “hopeful” and not know the prognosis. I say there are other things to hope for besides not dying. Hope that pain is under control. Hope that he can feel comfortable enough to enjoy his family. Hope that, when the time comes, he will enter hospice in a timely manner.

Meanwhile — he’s still here.

__________________

Author Chaplain Hank Dunn, MDiv, has sold over 4 million copies of his books Hard Choices for Loving People and Light in the Shadows (also available on Amazon).

Follow Hank: LinkedIn | Instagram | Facebook | YouTube

We were sitting in the upstairs bedroom of their suburban home. He was in a wheelchair, and I was sitting in front of him. His wife was in a chair on the other side of the room. I often ask patients, “Do you pray?” And like most everyone else, this man replied, “Yes.”

We were sitting in the upstairs bedroom of their suburban home. He was in a wheelchair, and I was sitting in front of him. His wife was in a chair on the other side of the room. I often ask patients, “Do you pray?” And like most everyone else, this man replied, “Yes.”

From a

From a  Both the patient and her husband assured me that she would get whatever pain medications she needed and that they have talked about those important things. I believed them on both counts.

Both the patient and her husband assured me that she would get whatever pain medications she needed and that they have talked about those important things. I believed them on both counts. I can understand that a person may not want to know their prognosis because predicting how much time a patient has is so difficult. A Facebook friend recently posted, “One year ago (May 23), I was told I had 6 months to live. I’m still here.”

I can understand that a person may not want to know their prognosis because predicting how much time a patient has is so difficult. A Facebook friend recently posted, “One year ago (May 23), I was told I had 6 months to live. I’m still here.” @hospicenursepenny’s thoughts on the importance of talking about it

@hospicenursepenny’s thoughts on the importance of talking about it This outlook did not come easy for her. This book is, in part, a memoir about how a troubled young mother survived her own addictions and reckless living. Her life story is woven into the fabric of a book to help people have a better death and, she hopes, have a better life.

This outlook did not come easy for her. This book is, in part, a memoir about how a troubled young mother survived her own addictions and reckless living. Her life story is woven into the fabric of a book to help people have a better death and, she hopes, have a better life. Questions and comments from Smith’s social media followers appear in Influencing Death, allowing segues to practical end-of-life advice. Here are just a few nuggets of Penny’s wisdom found in these pages:

Questions and comments from Smith’s social media followers appear in Influencing Death, allowing segues to practical end-of-life advice. Here are just a few nuggets of Penny’s wisdom found in these pages:

Nothing to Fear: Demystifying Death to Live More by Julie McFadden, RN, is the latest in a long line of books showing the way to a more peaceful and more meaningful dying experience. Why another death and dying book? Why not? Sitting at #8 on the New York Times “Advice” best-seller list, Nothing to Fear is full of advice about navigating the last six months of life under hospice care.

Nothing to Fear: Demystifying Death to Live More by Julie McFadden, RN, is the latest in a long line of books showing the way to a more peaceful and more meaningful dying experience. Why another death and dying book? Why not? Sitting at #8 on the New York Times “Advice” best-seller list, Nothing to Fear is full of advice about navigating the last six months of life under hospice care.

Throughout Nothing to Fear we see nurse Julie addressing spiritual concerns of her patients and their families. She devotes a whole chapter, “Deathbed Phenomena,” to stories about patients having visions of long dead relatives. Here’s her understanding of these experiences returning to her theme of the metaphor of birth:

Throughout Nothing to Fear we see nurse Julie addressing spiritual concerns of her patients and their families. She devotes a whole chapter, “Deathbed Phenomena,” to stories about patients having visions of long dead relatives. Here’s her understanding of these experiences returning to her theme of the metaphor of birth:

I am guessing if, during that last phone call, Favre asked, “Do you regret getting the chemo?” Keith might have responded, “Not at all.” Perhaps it bought him some time. Maybe, earlier in the treatment, he did not think it was causing “more damage… than the cancer.”

I am guessing if, during that last phone call, Favre asked, “Do you regret getting the chemo?” Keith might have responded, “Not at all.” Perhaps it bought him some time. Maybe, earlier in the treatment, he did not think it was causing “more damage… than the cancer.”