FORT BLAKELEY, ALA. March 1, 2022: What if your teenage son went off to war — fought in one battle — died in that battle — and then you find out his death was actually after the war had ended — AND your side lost the war? Today, we would say parents of these dead soldiers would have complicated grief. Indeed.

FORT BLAKELEY, ALA. March 1, 2022: What if your teenage son went off to war — fought in one battle — died in that battle — and then you find out his death was actually after the war had ended — AND your side lost the war? Today, we would say parents of these dead soldiers would have complicated grief. Indeed.

Alabama built a state park surrounding the site of the Battle of Fort Blakeley. Tonight, while camping, I will be sleeping in that park on the earth that received the blood of hundreds of dead and wounded Americans. That was in April, 1865, and this fort was the last line of defense for the vital port city of Mobile.

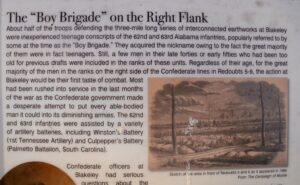

“Boy Brigade”

Display at battlefield

Late in the war, the Confederate States expanded the draft to include younger and older men. So, men in their forties and fifties were conscripted next to teenagers. There were so many teens in two Alabama infantries that some referred to them as the “Boy Brigade.”

Outnumbered 16,000 to 4,000, the Southern troops, including the Boy Brigade, built breastworks still visible today. April 9th was the first – and last – day of combat many young soldiers faced.

The final assault of the U.S. Army on the fort began at 5:30 PM on April 9th. But the Civil War effectively ended about two hours earlier when Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox in Virginia. News traveled slower then, and those poor souls fought a battle that had nothing to do with the outcome of the Civil War.

Complicated Grief

Many factors can complicate grief. Even in today’s world, many ponder the meaning of the death of someone they loved. Deaths by suicide, murder, drunk driving, or other accidents complicate the grief process that is painful even in the most “normal” circumstances.

Then there are the deaths of people with whom we have a conflicted relationship. The passing of a physically abusive father, a sexually exploitive uncle, or a verbally abusive mother can make the grief process most difficult.

I remember the daughter of a patient once said, “My mother never said, ‘I love you’ to me.” She told me that as we were making preparations for the mother’s funeral. Any chance of hearing, “I love you,” also died. We truly don’t know what goes into another’s grief.

All of a sudden, her story made sense

Another family comes to mind when I think about complicated grief. I was sitting vigil at a nursing home patient’s bedside with her daughter. The patient seemed like so many of these sweet old ladies who came to us with advanced dementia. Over the months that the patient was with us, I gathered her daughter’s story on her daily visits.

Photo by Ben White on Unsplash

At age 16, fifty years earlier, the daughter and her husband-to-be eloped under cover of darkness. She hid a packed suitcase under the front porch as she made her plans. Her younger brother happened upon the suitcase but kept the secret.

In the silence of our vigil, the daughter blurted out, “God. She was a hard woman.” Immediately, I thought to myself, “Now, I understand. The woman was abusive. THAT explains everything.”

When the daughter broke the silence as we sat by her mother, this story finally made sense. She was abused. The brother knew it. He conspired to help his sister make her escape. Yet fifty years later, here she was, sitting beside her mother as she lay dying. Complicated.

My mind comes back to those Confederate parents whose teenage sons went off to war, fought in one battle, and died in that battle after the war was over…and their side lost. Talk about complicated grief.

Grief can be complicated, indeed.

__________________________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

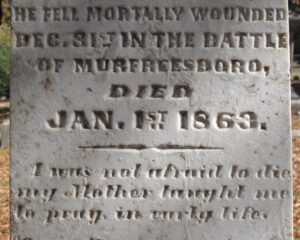

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be?

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be? Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride.

Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride. Was conscious

Was conscious The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man. “I know he would never want to be kept alive like this,” she said to me over the sound of a machine forcing air into her husband’s lungs. He lay motionless, eyes closed. He had been like this for months after arriving at the nursing home from the hospital.

“I know he would never want to be kept alive like this,” she said to me over the sound of a machine forcing air into her husband’s lungs. He lay motionless, eyes closed. He had been like this for months after arriving at the nursing home from the hospital. Since she was Jewish and asked this question, I gave her a copy of Rabbi Harold Kushner’s

Since she was Jewish and asked this question, I gave her a copy of Rabbi Harold Kushner’s

I listened to all 48 hours of this 900+ page book. It was worth every minute. Grant overcame so many setbacks to succeed as a general and President. Most significantly, according to Chernow, was his conquering his struggles with alcohol, a fact he does not mention in his own memoir. Had the Civil War never happened, history might not have known the name of U.S. Grant. It was his strategy to cut off the Southern states from beyond the Mississippi River with the fall of Vicksburg (July 1863), send Sherman through Georgia (1864), and capture Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. There was no finer moment in his life than when he offered generous terms of surrender to Lee. He hoped to begin the healing of a fractured nation. Sadly, as President, he had to fight the South again as it rose in the K.K.K. We are fortunate, as a nation, that Grant and Lincoln rose to the top when we needed them.

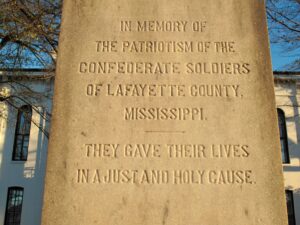

I listened to all 48 hours of this 900+ page book. It was worth every minute. Grant overcame so many setbacks to succeed as a general and President. Most significantly, according to Chernow, was his conquering his struggles with alcohol, a fact he does not mention in his own memoir. Had the Civil War never happened, history might not have known the name of U.S. Grant. It was his strategy to cut off the Southern states from beyond the Mississippi River with the fall of Vicksburg (July 1863), send Sherman through Georgia (1864), and capture Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. There was no finer moment in his life than when he offered generous terms of surrender to Lee. He hoped to begin the healing of a fractured nation. Sadly, as President, he had to fight the South again as it rose in the K.K.K. We are fortunate, as a nation, that Grant and Lincoln rose to the top when we needed them. Author Ty Seidule was born on July 3rd into a family culture steeped in the myth of righteous cause for which we Southerners fought. When people said, “too bad you weren’t born on the 4th,” he’d reply that he was glad to have been born on the day of Pickett’s charge (there it is again). Seidule rose through the ranks in the U.S. Army and taught at West Point. Through his academic research and soul-searching, he concluded that the “lost cause” myth of the South was wrong. According to Seidule, the Civil War was about slavery and the Confederate soldiers who took up arms against the U.S. government were traitors. He makes a compelling argument that we no longer need to honor these traitors with monuments or U.S. Army bases.

Author Ty Seidule was born on July 3rd into a family culture steeped in the myth of righteous cause for which we Southerners fought. When people said, “too bad you weren’t born on the 4th,” he’d reply that he was glad to have been born on the day of Pickett’s charge (there it is again). Seidule rose through the ranks in the U.S. Army and taught at West Point. Through his academic research and soul-searching, he concluded that the “lost cause” myth of the South was wrong. According to Seidule, the Civil War was about slavery and the Confederate soldiers who took up arms against the U.S. government were traitors. He makes a compelling argument that we no longer need to honor these traitors with monuments or U.S. Army bases. Like most, I knew of Chamberlain for only a few hours of his life on July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg. He commanded the 20th Maine at the extreme end of the Union line on Little Round Top. His troops were under repeated assault and running out of ammunition. Had he failed in defending his position, the entire U.S. Army on the field could have been destroyed in a flanking maneuver by the advancing Confederates. He ordered his men to fix bayonets, and they charged downhill, capturing more than 100 Southerners and saving the day. Many books and movies have captured this one moment. He was a college professor before the war. He became a college president and served four years as governor after returning to Maine. One other moving scene in Chamberlain’s military career was the last day of the war. He was the commander in charge of the ceremony at Appomattox, where the defeated rebels would surrender their arms. In the spirit that Grant set in the terms of surrender, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute their defeated foes, now countrymen once again.

Like most, I knew of Chamberlain for only a few hours of his life on July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg. He commanded the 20th Maine at the extreme end of the Union line on Little Round Top. His troops were under repeated assault and running out of ammunition. Had he failed in defending his position, the entire U.S. Army on the field could have been destroyed in a flanking maneuver by the advancing Confederates. He ordered his men to fix bayonets, and they charged downhill, capturing more than 100 Southerners and saving the day. Many books and movies have captured this one moment. He was a college professor before the war. He became a college president and served four years as governor after returning to Maine. One other moving scene in Chamberlain’s military career was the last day of the war. He was the commander in charge of the ceremony at Appomattox, where the defeated rebels would surrender their arms. In the spirit that Grant set in the terms of surrender, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute their defeated foes, now countrymen once again. With all believing God is on their side in a war, it is especially hard for the losers to explain what happened. This presented an exceptional problem for the dominant version of Christianity in the South (evangelical Protestant). In their view, the Yankees were more secular, more liberal, more urban, and less devoted Christians. This book by Charles Wilson, a former professor at the University of Mississippi and fellow church member with me in Oxford, explains the mental and theological gymnastics my Southern ancestors went through to explain how God was on their side. God sided with the South because their cause was righteous, but the North’s industrial strength was too much even for God. Dr. Wilson recently gave three lectures on this topic at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in

With all believing God is on their side in a war, it is especially hard for the losers to explain what happened. This presented an exceptional problem for the dominant version of Christianity in the South (evangelical Protestant). In their view, the Yankees were more secular, more liberal, more urban, and less devoted Christians. This book by Charles Wilson, a former professor at the University of Mississippi and fellow church member with me in Oxford, explains the mental and theological gymnastics my Southern ancestors went through to explain how God was on their side. God sided with the South because their cause was righteous, but the North’s industrial strength was too much even for God. Dr. Wilson recently gave three lectures on this topic at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in

A

A

The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published an opinion piece,

The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published an opinion piece,

Last week,

Last week,