Photo by Vidal Balielo Jr. via Pexels.com

The man was riddled with cancer. The paramedics continued CPR as they wheeled him out of his nursing home room. I drove his wife to the emergency room. This is what the family wanted, although I am not sure the patient would have chosen it. When the doc came to the waiting room to tell the family he died, they congratulated themselves on “trying everything.”

Sadly, aggressive care in the last days of life is all too common. Perhaps, my experience with this patient was an extreme example. Aggressive care can include an ICU stay, surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy. New research shows that about 60% of elderly Americans with metastatic cancer receive some sort of aggressive care in the last 30 days of life.

60% of elderly, advanced cancer patients receive aggressive life-saving attempts in the last month of life

Photo by Matej via Pexels.com

This research was recently published in JAMA Network Open and looked at the last 30 days in the lives of 146,329 people who were over 65 and had a diagnosis of metastatic cancer, in other words, very sick, frail elderly folks with an average age of 78.2 years.

I was put onto this research by a great article from Paula Span in the New York Times. She writes a regular piece called, “The New Old Age,” and this was one in her series. What is not clear from the research is “Why?” Why are so many, obviously dying old folks being dragged through more treatments which are normally reserved for those seeking cure?

Some may want this treatment, but I doubt it

Photo by Kampus Production via Pexels.com

It is true that some of these aggressive treatments can be considered palliative, for example, radiation to reduce the size of a tumor and hopefully reduce pain. It is also true, that some of this aggressive treatment is actually what the patient wanted. Perhaps, they were made fully aware of their grave condition but chose treatment that had little chance of helping them. Both of these possibilities are probably in a small minority of this aggressive care.

Spirituality raises its head again

The JAMA study concluded, “The reasons for aggressive end-of-life care are multifactorial, including family involvement, religion and spirituality, patient preferences, patient-clinician communication, and health care delivery systems.” I would add, the default mode in our healthcare system is to do stuff, when faced with a problem. That “stuff” is usually doing more of the same rather than shifting to comfort care only.

My chaplain antennae always perk up when I see “religion and spirituality” mentioned in any medical journal article. I am back to my oft-repeated premise — for patients and families, end-of-life decisions are primarily emotional and spiritual. People need to learn when it is time to let go and just let things be.

_________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

The patient had left verbal and written instructions that she did not want to have life-saving treatments when she was dying. A “No CPR” order was on her chart. Knowing her daughter’s feelings, the old lady chose her son as her power of attorney. She conspicuously omitted any mention of her daughter in the document.

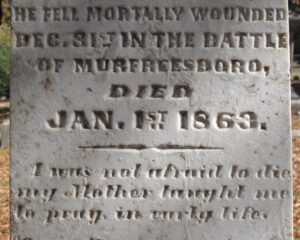

The patient had left verbal and written instructions that she did not want to have life-saving treatments when she was dying. A “No CPR” order was on her chart. Knowing her daughter’s feelings, the old lady chose her son as her power of attorney. She conspicuously omitted any mention of her daughter in the document. A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be?

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be? Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride.

Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride. Was conscious

Was conscious The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man. “I know he would never want to be kept alive like this,” she said to me over the sound of a machine forcing air into her husband’s lungs. He lay motionless, eyes closed. He had been like this for months after arriving at the nursing home from the hospital.

“I know he would never want to be kept alive like this,” she said to me over the sound of a machine forcing air into her husband’s lungs. He lay motionless, eyes closed. He had been like this for months after arriving at the nursing home from the hospital. Since she was Jewish and asked this question, I gave her a copy of Rabbi Harold Kushner’s

Since she was Jewish and asked this question, I gave her a copy of Rabbi Harold Kushner’s

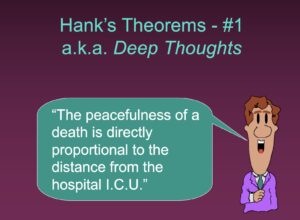

About that same time, I started traveling around the country making presentations to healthcare professionals. My most popular talk, “Helping Patients and Families with End-of-Life Decisions,” includes a series of slides with “Hank’s Theorems” on various end-of-life issues. The first slide says, “The peacefulness of a death is directly proportional to the distance from the hospital ICU.”

About that same time, I started traveling around the country making presentations to healthcare professionals. My most popular talk, “Helping Patients and Families with End-of-Life Decisions,” includes a series of slides with “Hank’s Theorems” on various end-of-life issues. The first slide says, “The peacefulness of a death is directly proportional to the distance from the hospital ICU.”

In 2002, the National Kidney Foundation published clinical practice guidelines on the evaluation, classification, and stratification of chronic kidney disease (CKD). These guidelines were based on levels found in a patient’s blood chemistry. Patients are classified as “normal/mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” Those with more severe conditions may be put on dialysis.

In 2002, the National Kidney Foundation published clinical practice guidelines on the evaluation, classification, and stratification of chronic kidney disease (CKD). These guidelines were based on levels found in a patient’s blood chemistry. Patients are classified as “normal/mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” Those with more severe conditions may be put on dialysis. In 2017,

In 2017,