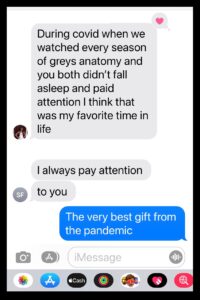

Imagine my surprise at getting a text from my youngest daughter, Katie, that started and ended this way: “During COVID… I think that was my favorite time in life.” Of course, it was everything in between that beginning and ending that tells the story.

Most of Generation Z spent their last year of college (2020-21) attending class in front of a computer screen. Katie was included in that cohort. It was our good fortune, in 2019, to have moved to Oxford, Mississippi, where she was going to school. Although she shared a townhouse with some friends, she and Charlie, her Cavalier Spaniel,spent a great deal of time in our home.

My wife and I tend to be news junkies. Each evening we record the ABC World News Tonight and the PBS NewsHour. And, each evening, we watch both, mercifully skipping the commercials. Katie did not share our news addiction and turned us on to a “new drug” — Grey’s Anatomy.

My wife and I tend to be news junkies. Each evening we record the ABC World News Tonight and the PBS NewsHour. And, each evening, we watch both, mercifully skipping the commercials. Katie did not share our news addiction and turned us on to a “new drug” — Grey’s Anatomy.

Thanks to COVID, we were not going out, so it was a binge of 17 seasons and close to 400 episodes. We took a pass on our basketball and baseball season tickets and went to med school. Twice, late in 2020, I blogged about Grey’s — “Grey’s Anatomy and CPR on Television” and “The Spiritual Side of Grey’s Anatomy.”

I started that first blog, “True confession: I have joined my 22-year-old daughter in binge-watching Grey’s Anatomy during the pandemic. Over 300 episodes viewed and counting. I now know about ‘10-blade,’ ‘clear!’ and the importance of declaring ‘time of death.’ Also, I never knew there was so much romance and sex going on in hospital supply closets and on-call sleeping rooms. Now I know.”

Last week, out of the blue, Katie texted us, “During covid when we watched every season of Grey’s Anatomy and you both didn’t fall asleep and paid attention I think that was my favorite time in life.” (I will not comment on the falling asleep or paying attention part, but I really did enjoy the series.)

Last week, out of the blue, Katie texted us, “During covid when we watched every season of Grey’s Anatomy and you both didn’t fall asleep and paid attention I think that was my favorite time in life.” (I will not comment on the falling asleep or paying attention part, but I really did enjoy the series.)

I know, for many people, the pandemic was horrible. People died. People were exhausted. There was NO silver lining for them. To be clear, Katie did not qualify the family-watching-Grey’s as the best thing about COVID. She was more expansive — watching Grey’s with us was her “favorite time in life.”

Regardless, I’m grateful we got to make the best of a bad situation. We salvaged some uninterrupted family time and made memories with our daughter. Binge-watching TV was the silver lining of the pandemic. At least, it was for us.

________________________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

So, on Thanksgiving 1996, 42 years after his death, we had a funeral for my brother. Mom, Dad in his wheelchair, my brother, his wife, my daughter, and I gathered at the grave. I read the words of committal (“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”) and Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), we said the Lord’s Prayer, and I stammered through a prayer about Randy.

So, on Thanksgiving 1996, 42 years after his death, we had a funeral for my brother. Mom, Dad in his wheelchair, my brother, his wife, my daughter, and I gathered at the grave. I read the words of committal (“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”) and Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), we said the Lord’s Prayer, and I stammered through a prayer about Randy.

Not to worry! This progressive, free-thinking university city put up a sign to warn me: “ICE MAY EXIST,” it read. I thought, “This is SO Boulder!”

Not to worry! This progressive, free-thinking university city put up a sign to warn me: “ICE MAY EXIST,” it read. I thought, “This is SO Boulder!”