“I made a mistake. I made the wrong decision,” the wife of the recently deceased man said.

Several years ago, I spoke at the Centra Hospital in Lynchburg, Virginia. There were about 50 people in the room, including members of the clergy, physicians, nurses, social workers, and just plain folks. I divided my presentation, the first half devoted to helping patients and families make end-of-life decisions, and the second half to the emotional and spiritual issues at the end of life.

Several years ago, I spoke at the Centra Hospital in Lynchburg, Virginia. There were about 50 people in the room, including members of the clergy, physicians, nurses, social workers, and just plain folks. I divided my presentation, the first half devoted to helping patients and families make end-of-life decisions, and the second half to the emotional and spiritual issues at the end of life.

When I invited the audience to speak, a lady raised her hand and told her friend’s story. Her friend’s husband had been in a nursing home and on a feeding tube. He was not considered to have the capacity to make his own medical decisions, so all the medical treatment decisions rested on his wife.

On more than one occasion, the patient pulled out the feeding tube. This lady suggested to her friend that perhaps her husband was saying he did not want the feeding tube. Her friend always responded, “He doesn’t know what he is doing.” They always reinserted the tube and resumed the feedings.

“I should have left the tube out and let him die sooner.”

About six months after the patient died, the lady visited her friend. The now-widow said, “I made a mistake. I made the wrong decision. I should have left the tube out and let him die sooner.”

About six months after the patient died, the lady visited her friend. The now-widow said, “I made a mistake. I made the wrong decision. I should have left the tube out and let him die sooner.”

At times, I have heard other family caregivers express similar regrets about decisions made. “We shouldn’t have sent mom back to the ICU.” “I wish we had never started the feeding tube.” “We kept the chemo going way too long.”

You can never make the wrong decision

When I hear remorse like this, I always tell people, “You can never make the wrong decision. You make the best decision you can with the information you have at the time.” In my 28 years of being close to decision-makers, I have never thought someone made a decision intending to harm a patient. People always want the best for the patient. It is only in looking back that they say a decision was a mistake.

I even say “you can’t make a wrong decision” to people in the throes of a decision-making process. I hope to ease the burden they are placing on themselves. These choices can be hard enough. I want to assure these burdened families they can’t make the wrong decision. You just do the best you can with the information you have at the time.

[A version of this blog post appeared in 2011.]

________________________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

Photo by Nik Shuliahin on Unsplash

Recently,

Recently,  Then, of course, “happy” is

Then, of course, “happy” is  Recently, I

Recently, I

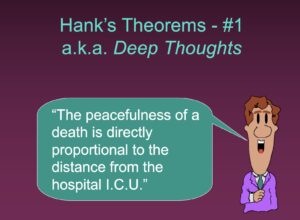

About that same time, I started traveling around the country making presentations to healthcare professionals. My most popular talk, “Helping Patients and Families with End-of-Life Decisions,” includes a series of slides with “Hank’s Theorems” on various end-of-life issues. The first slide says, “The peacefulness of a death is directly proportional to the distance from the hospital ICU.”

About that same time, I started traveling around the country making presentations to healthcare professionals. My most popular talk, “Helping Patients and Families with End-of-Life Decisions,” includes a series of slides with “Hank’s Theorems” on various end-of-life issues. The first slide says, “The peacefulness of a death is directly proportional to the distance from the hospital ICU.”

The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published an opinion piece,

The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published an opinion piece,

In 2002, the National Kidney Foundation published clinical practice guidelines on the evaluation, classification, and stratification of chronic kidney disease (CKD). These guidelines were based on levels found in a patient’s blood chemistry. Patients are classified as “normal/mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” Those with more severe conditions may be put on dialysis.

In 2002, the National Kidney Foundation published clinical practice guidelines on the evaluation, classification, and stratification of chronic kidney disease (CKD). These guidelines were based on levels found in a patient’s blood chemistry. Patients are classified as “normal/mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” Those with more severe conditions may be put on dialysis. In 2017,

In 2017,