FORT BLAKELEY, ALA. March 1, 2022: What if your teenage son went off to war — fought in one battle — died in that battle — and then you find out his death was actually after the war had ended — AND your side lost the war? Today, we would say parents of these dead soldiers would have complicated grief. Indeed.

FORT BLAKELEY, ALA. March 1, 2022: What if your teenage son went off to war — fought in one battle — died in that battle — and then you find out his death was actually after the war had ended — AND your side lost the war? Today, we would say parents of these dead soldiers would have complicated grief. Indeed.

Alabama built a state park surrounding the site of the Battle of Fort Blakeley. Tonight, while camping, I will be sleeping in that park on the earth that received the blood of hundreds of dead and wounded Americans. That was in April, 1865, and this fort was the last line of defense for the vital port city of Mobile.

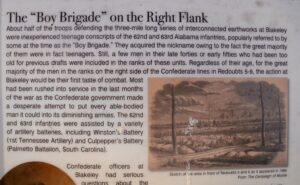

“Boy Brigade”

Display at battlefield

Late in the war, the Confederate States expanded the draft to include younger and older men. So, men in their forties and fifties were conscripted next to teenagers. There were so many teens in two Alabama infantries that some referred to them as the “Boy Brigade.”

Outnumbered 16,000 to 4,000, the Southern troops, including the Boy Brigade, built breastworks still visible today. April 9th was the first – and last – day of combat many young soldiers faced.

The final assault of the U.S. Army on the fort began at 5:30 PM on April 9th. But the Civil War effectively ended about two hours earlier when Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox in Virginia. News traveled slower then, and those poor souls fought a battle that had nothing to do with the outcome of the Civil War.

Complicated Grief

Many factors can complicate grief. Even in today’s world, many ponder the meaning of the death of someone they loved. Deaths by suicide, murder, drunk driving, or other accidents complicate the grief process that is painful even in the most “normal” circumstances.

Then there are the deaths of people with whom we have a conflicted relationship. The passing of a physically abusive father, a sexually exploitive uncle, or a verbally abusive mother can make the grief process most difficult.

I remember the daughter of a patient once said, “My mother never said, ‘I love you’ to me.” She told me that as we were making preparations for the mother’s funeral. Any chance of hearing, “I love you,” also died. We truly don’t know what goes into another’s grief.

All of a sudden, her story made sense

Another family comes to mind when I think about complicated grief. I was sitting vigil at a nursing home patient’s bedside with her daughter. The patient seemed like so many of these sweet old ladies who came to us with advanced dementia. Over the months that the patient was with us, I gathered her daughter’s story on her daily visits.

Photo by Ben White on Unsplash

At age 16, fifty years earlier, the daughter and her husband-to-be eloped under cover of darkness. She hid a packed suitcase under the front porch as she made her plans. Her younger brother happened upon the suitcase but kept the secret.

In the silence of our vigil, the daughter blurted out, “God. She was a hard woman.” Immediately, I thought to myself, “Now, I understand. The woman was abusive. THAT explains everything.”

When the daughter broke the silence as we sat by her mother, this story finally made sense. She was abused. The brother knew it. He conspired to help his sister make her escape. Yet fifty years later, here she was, sitting beside her mother as she lay dying. Complicated.

My mind comes back to those Confederate parents whose teenage sons went off to war, fought in one battle, and died in that battle after the war was over…and their side lost. Talk about complicated grief.

Grief can be complicated, indeed.

__________________________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

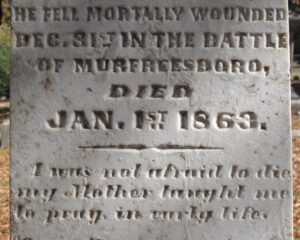

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be?

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be? Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride.

Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride. Was conscious

Was conscious The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

“Charlie” was not a very creative name, but it just seemed to fit a male King Charles Spaniel. At first, we crated him at night. After weeks of barking, he finally settled into his crate and his place at home. Until…

“Charlie” was not a very creative name, but it just seemed to fit a male King Charles Spaniel. At first, we crated him at night. After weeks of barking, he finally settled into his crate and his place at home. Until… Charlie joined Katie in Oxford her second year at Ole Miss, where he supported her during roommate issues and dating cycles. Their deep bond reached new depths. A dog just loves unconditionally.

Charlie joined Katie in Oxford her second year at Ole Miss, where he supported her during roommate issues and dating cycles. Their deep bond reached new depths. A dog just loves unconditionally.

On Sunday afternoon, my wife and I were pulling into the Walmart parking lot, and she blurted out, “Katie has to come home tonight.” It was a mother’s flash of insight for her soon-to-be grieving daughter. She called Katie and told her to get to National airport and get on a plane. I picked her up in Memphis with Charlie a few hours later. They slept together on our bedroom floor that night before she returned to D.C., Monday. In the car on the way to the Memphis airport, she “Snapped” a photo to friends, “my last photo I’ll ever take with my baby.” Indeed, it was.

On Sunday afternoon, my wife and I were pulling into the Walmart parking lot, and she blurted out, “Katie has to come home tonight.” It was a mother’s flash of insight for her soon-to-be grieving daughter. She called Katie and told her to get to National airport and get on a plane. I picked her up in Memphis with Charlie a few hours later. They slept together on our bedroom floor that night before she returned to D.C., Monday. In the car on the way to the Memphis airport, she “Snapped” a photo to friends, “my last photo I’ll ever take with my baby.” Indeed, it was.

I was here to ponder how one place can hold so much grief and healing.

I was here to ponder how one place can hold so much grief and healing.

It turns out her idea was masterful. The Wall has become a place of reflection and healing, a public place to grieve privately. Annually, millions walk the path by the wall in silence, as if in a sacred space — indeed it is. Grown men weep as they touch the name of a fallen comrade. Children visit the names of fathers they never knew.

It turns out her idea was masterful. The Wall has become a place of reflection and healing, a public place to grieve privately. Annually, millions walk the path by the wall in silence, as if in a sacred space — indeed it is. Grown men weep as they touch the name of a fallen comrade. Children visit the names of fathers they never knew. The story is about loss and backpacking, two abiding interests in my life. I’d probably write favorably of anyone who takes their grief on a 1,100-mile backpacking trip. Cheryl Strayed did and wrote about it.

The story is about loss and backpacking, two abiding interests in my life. I’d probably write favorably of anyone who takes their grief on a 1,100-mile backpacking trip. Cheryl Strayed did and wrote about it. There are many moving passages in the book, but I was caught by one line on the next-to-last page of the book. Cheryl touches the bridge on the Columbia River, the site at the end of her journey. She walks back to an ice cream stand to buy herself a treat with the last two dollars she has to her name. She enjoys her ice cream, chatting with a lawyer from Portland who stops for ice cream, too. She says goodbye to him and

There are many moving passages in the book, but I was caught by one line on the next-to-last page of the book. Cheryl touches the bridge on the Columbia River, the site at the end of her journey. She walks back to an ice cream stand to buy herself a treat with the last two dollars she has to her name. She enjoys her ice cream, chatting with a lawyer from Portland who stops for ice cream, too. She says goodbye to him and

So, on Thanksgiving 1996, 42 years after his death, we had a funeral for my brother. Mom, Dad in his wheelchair, my brother, his wife, my daughter, and I gathered at the grave. I read the words of committal (“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”) and Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), we said the Lord’s Prayer, and I stammered through a prayer about Randy.

So, on Thanksgiving 1996, 42 years after his death, we had a funeral for my brother. Mom, Dad in his wheelchair, my brother, his wife, my daughter, and I gathered at the grave. I read the words of committal (“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”) and Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), we said the Lord’s Prayer, and I stammered through a prayer about Randy.