Me: “Hello, this is the chaplain, Hank. I would like to come by your home for a visit Tuesday, at 10. Would that work for you?”

Patient: “Oh, hi… (pause) No, not then. How ‘bout Thursday at 10?”

Me: “Great, see you then.”

I thought of this conversation as I was digging down into a Canadian governmental report.

Why are we so different than our Canadian neighbors? We share a 5,525-mile-long border yet, in response to one question, we are miles apart. Do we really live and die that differently?

I have this nerdy side of myself. I read through medical journal articles and government reports looking for insights into all things end-of-life. The government of Canada and the State of Oregon recently released their annual reports on Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) or, in Oregon, Death with Dignity. These are the rebranded names for what used to be called Physician Assisted Suicide.

One number jumped out

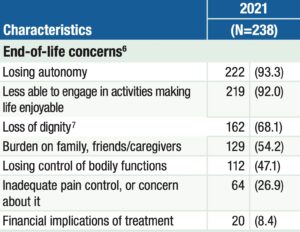

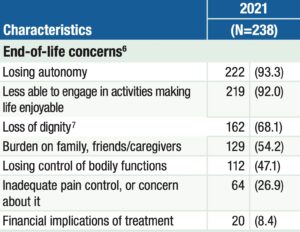

End-of-life concerns: U.S.A.

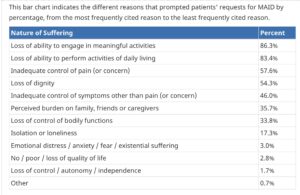

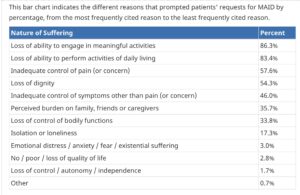

End-of-life concerns: CANADA

I’m reading through these reports and one number jumped out at me. Physicians who aided these terminally ill patients in hastening their deaths with medications were asked, “Why did the patient want to end their life by taking a lethal medication?”

In Oregon, the number one reason out of seven choices that patients gave was concern over “Losing Autonomy.” 93.3% of these patients listed that as one of their end-of-life concerns. In Canada, at the BOTTOM of a list of eleven possible concerns, “Loss of control / autonomy / independence” is only mentioned by 1.7% patients.

My interest was piqued by that “autonomy” difference. So, I contacted my friend, Tim Ward, who is now writing about his travels in Europe. He and his wife are taking “senior gap year” as in “senior citizen gap year” traveling. Tim is a Canadian by birth and has recently become a U.S. citizen.

He emailed back from Paris, “It might be that in Canada, autonomy is less of a value than, say, meaningful social connection” and “the rugged individualism of the West is part of eastern Oregon’s make up.”

Individualism/Autonomy vs. social connection

I think he is on to something here. For example, the social connection vs. autonomy shows up in how we provide healthcare. In the U.S. we do not provide universal healthcare, Canada does. There is no for-profit health insurance industry in Canada, yet everyone has access to healthcare. The U.S. system is built upon a for-profit system that leaves 8.6% (28 million) of our fellow citizens without health insurance. How we provide healthcare is just the most glaring example of how we value individual choices over the common good. Also, the social safety net is very weak for the poorest among us in the U.S. — as we witnessed in the pandemic.

I got curious about where in the world people are the happiest. Turns out, Canada (#15) and the U.S. (#16) show up next to each other in a recent ranking of the happiest countries. The top countries are in northern Europe.

From the Gallup World Poll report, “[Finland] and its neighbors Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Iceland all score very well on the measures the report uses to explain its findings: healthy life expectancy, GDP per capita, social support in times of trouble, low corruption and high social trust, generosity in a community where people look after each other and freedom to make key life decisions.”

Critics would say that’s true, they may be happier, but they pay very high taxes. The countries highest on the “Happiest” list are often labeled as “socialist” by those same critics. That’s a discussion for another time and place. The point here is that the autonomy cherished by U.S. citizens shows up in less “social support.”

The myth of the cowboy

Photo by Taylor Brandon on Unsplash

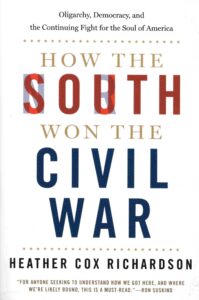

Tim’s other point, about “rugged individualism,” caught my eye because of another nerdy side of me — I read books about the American South and how we got the way we are down here. Currently, I am into How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America by Heather Cox Richardson.

Richardson is a historian with 1.6 million followers on Facebook. She writes on that platform often and produces long videos discussing various history-related topics. In this current book she explains the growth of the “myth of the cowboy,” the ultimate “rugged individual.” According to her, since the late 19th century, Americans have bought into this idea that anybody can attain whatever they want, that this country was built by autonomous “rugged individualists.” This is a myth because wealth actually went to a few elites from the days of the Founders to today.

Our founding documents lay out this contradiction in spades. The same property-owning White men who wrote, “All men are created equal,” enslaved Black people and did not give women or poor Whites a vote. We, as a nation, have been struggling with this contradiction ever since. Although Canadians do not have the history of slavery we do, we both share shameful treatment of indigenous peoples. Also, a discussion for another time and place. The point here is lionizing the “rugged individual” can show up as valuing autonomy at the expense of social connection.

Pastoral care at the end of life and autonomy

The phone exchange with the patient was typical of many we had over the months I was his chaplain. He ALWAYS chose another time. As a chaplain for those at the end of their lives I am always looking for ways to enhance autonomy, because I know it is so important to most of us. I gladly changed my plans. I figured this was my little way of affirming his autonomy.

________________________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

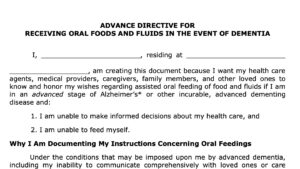

Update our advance directives. I wrote a blog recently about Voluntary Stopping Eating and Drinking (VSED) by advance directive. I want to add instructions on when to stop hand feeding me if I have advanced dementia. Putting this in writing can be very easy to do with samples I linked in the blog. Then, of course, we need to have two friends over to witness my signature.

Update our advance directives. I wrote a blog recently about Voluntary Stopping Eating and Drinking (VSED) by advance directive. I want to add instructions on when to stop hand feeding me if I have advanced dementia. Putting this in writing can be very easy to do with samples I linked in the blog. Then, of course, we need to have two friends over to witness my signature. Continue to gather my “memoir” for my kids and grands. I wrote a blog around my birthday in 2021 about “keeping your regret list short.” It was kind of a “bucket list” thingy and I mentioned the notebooks I had gathered for my children and their children. Well, I have written more since then, so I need to keep on gathering. I also print my favorite quotable-quotes file (36 pages long). Interestingly, I found among dad’s papers, a notebook he kept of his favorite quotes, probably dating from the 1950s. When I started my own compilation of quotes, I had no idea he had done the same.

Continue to gather my “memoir” for my kids and grands. I wrote a blog around my birthday in 2021 about “keeping your regret list short.” It was kind of a “bucket list” thingy and I mentioned the notebooks I had gathered for my children and their children. Well, I have written more since then, so I need to keep on gathering. I also print my favorite quotable-quotes file (36 pages long). Interestingly, I found among dad’s papers, a notebook he kept of his favorite quotes, probably dating from the 1950s. When I started my own compilation of quotes, I had no idea he had done the same.

I posted a

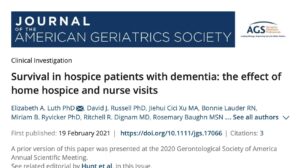

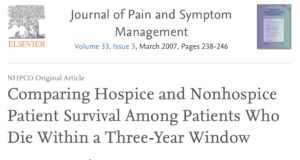

I posted a  It makes no sense that hospice would want to hasten a patient’s death. The more days the patient is on hospice, the more reimbursement the hospice receives. It is totally against their financial interest to hasten death.

It makes no sense that hospice would want to hasten a patient’s death. The more days the patient is on hospice, the more reimbursement the hospice receives. It is totally against their financial interest to hasten death. Many studies confirm that hospice patients live longer than nonhospice patients suffering from the same disease.

Many studies confirm that hospice patients live longer than nonhospice patients suffering from the same disease.

Rosemary Bowen, at 94, was living independently. She said she had had a wonderful life and did not look forward to a long, slow decline toward death. For years, she had been telling her children, “That her life would not be worth living if she had to depend on caretakers to feed her, dress her, and take her to the toilet.” Then, it happened. She fractured her back and went to rehab but was unable to live independently. That was enough for her.

Rosemary Bowen, at 94, was living independently. She said she had had a wonderful life and did not look forward to a long, slow decline toward death. For years, she had been telling her children, “That her life would not be worth living if she had to depend on caretakers to feed her, dress her, and take her to the toilet.” Then, it happened. She fractured her back and went to rehab but was unable to live independently. That was enough for her. Do not try this without medical support. Rosemary was able to get a hospice to care for her in her last days. Palliative care is also available to ease burdensome symptoms like pain and thirst. See

Do not try this without medical support. Rosemary was able to get a hospice to care for her in her last days. Palliative care is also available to ease burdensome symptoms like pain and thirst. See

I have just discovered two great videos with Dr. Michael Greger discussing this very topic. Each video is less than seven minutes and worth every minute of your time. One is called

I have just discovered two great videos with Dr. Michael Greger discussing this very topic. Each video is less than seven minutes and worth every minute of your time. One is called  In his second video he referred to a study reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. “In fact, the most expensive drug they looked at, the one costing $169,836 a year, did not improve overall survival at all, and actually worsened quality of life. That’s $169,000 just to make you feel worse with no benefit. Why pay a penny for a treatment that doesn’t actually help?”

In his second video he referred to a study reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. “In fact, the most expensive drug they looked at, the one costing $169,836 a year, did not improve overall survival at all, and actually worsened quality of life. That’s $169,000 just to make you feel worse with no benefit. Why pay a penny for a treatment that doesn’t actually help?” The patient had left verbal and written instructions that she did not want to have life-saving treatments when she was dying. A “No CPR” order was on her chart. Knowing her daughter’s feelings, the old lady chose her son as her power of attorney. She conspicuously omitted any mention of her daughter in the document.

The patient had left verbal and written instructions that she did not want to have life-saving treatments when she was dying. A “No CPR” order was on her chart. Knowing her daughter’s feelings, the old lady chose her son as her power of attorney. She conspicuously omitted any mention of her daughter in the document. How many times have we seen in an obituary, “He died peacefully at home with his family gathered around him.” Families wear this as a badge of honor. They provided the best of care and met the patient’s wishes to remain at home.

How many times have we seen in an obituary, “He died peacefully at home with his family gathered around him.” Families wear this as a badge of honor. They provided the best of care and met the patient’s wishes to remain at home.