While we were planning a funeral for her 22-year-old son, Scott, she put down her beer, took the cigarette from her lips, and said, “So, I remind you of the Virgin Mary?” A lighter moment amid grief. Scott died from a long and debilitating illness. He may have weighed 80 pounds in the end.

I lived a few doors down from Scott and his family for four years. His sisters babysat my kids. I was Scott’s den leader in Cub Scouts. As disease ravaged his young body, Scott graduated from college in a wheelchair. I was so privileged to be a part of his care.

I lived a few doors down from Scott and his family for four years. His sisters babysat my kids. I was Scott’s den leader in Cub Scouts. As disease ravaged his young body, Scott graduated from college in a wheelchair. I was so privileged to be a part of his care.

In Scott’s last days, one of my fellow chaplains called me as he was preparing to leave town on vacation. He was aware I was an old friend of Scott and his family. He asked if I could check in on Scott and even do the funeral if he died. I was glad to do it.

On my second visit to see Scott in our hospice in-patient unit, I could tell he was taking his last breaths. His mom and sisters were at his side. He had been in such great pain that he was totally sedated. His breathing stopped. The tears flowed after months of anticipating this moment.

I summoned the nurse. She asked Scott’s mother, “Would you like to hold him?” Of course, she would. It had been months since she could even touch him because of the pain.

The nurse gathered the sheet around Scott’s body and placed him in his mother’s lap. She held him tenderly, stroking his face, and telling him of her love. I later told a friend of the scene and he said it reminded him of Michelangelo’s Pietà. It was indeed a very similar scene, a mother cradling the body of her broken son.

A few days later, I told Scott’s mother about my friend’s comment. That’s when, beer and cigarette in hand, she said, “So, I remind you of the Virgin Mary?”

This experience came to mind as I read a Washington Post story about the stunning rise in the use of cremation. Now, 57% of our dead are cremated compared to 27% just two decades ago. Along with the traditional casket burials, Americans are having less to do with the dead. Many have no rituals at all surrounding the death of one they love.

Undertaker Author Thomas Lynch

Many want to avoid the greater expense of a traditional funeral and burial. But, perhaps, many want to avoid being around the dead body or the emotional strain of the rituals. Thomas Lynch, a Michigan poet and funeral director of 50 years said in the Post article, “People want the body disappeared, pretty much. I think it reminds us of what we lost.” In the United States, Lynch notes, “this is the first generation of our species that tries to deal with death without dealing with the dead.”

I will say, there is another trend that runs counter to this criticism that we Americans are avoiding the dead. More and more people are dying at home which gives the family the opportunity to be with the departed. A century ago, almost everyone died at home. This can provide that ritual lost with the demise of the traditional funeral.

Rest in peace.

________________________________________

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

This is how David Brooks starts a recent

This is how David Brooks starts a recent  Gradually, for some people, a new core narrative emerges answering the question, “What am I to do with this unexpected life?” It’s not that the facts are different, but a person can step back and see them differently. New frameworks are imposed, which reorganize the relationship between the events of a life. Spatial metaphors are helpful here: I was in a dark wood. This train is not turning around. I’m climbing a second mountain.

Gradually, for some people, a new core narrative emerges answering the question, “What am I to do with this unexpected life?” It’s not that the facts are different, but a person can step back and see them differently. New frameworks are imposed, which reorganize the relationship between the events of a life. Spatial metaphors are helpful here: I was in a dark wood. This train is not turning around. I’m climbing a second mountain.

“The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action.… Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.… We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

“The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action.… Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.… We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. I’ve had the opportunity to officiate many funerals over the years. This was supposed to be one of the “easy” ones. The dead man’s family had a relative who once was a member of my church in Vienna, Virginia, back in the day. None of the family attended that church now — or any church. So, when the man died suddenly of a heart attack at 64, they turned to us for a minister to conduct the service — kind of a rent-a-preacher.

I’ve had the opportunity to officiate many funerals over the years. This was supposed to be one of the “easy” ones. The dead man’s family had a relative who once was a member of my church in Vienna, Virginia, back in the day. None of the family attended that church now — or any church. So, when the man died suddenly of a heart attack at 64, they turned to us for a minister to conduct the service — kind of a rent-a-preacher.

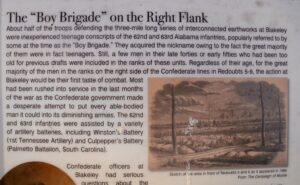

FORT BLAKELEY, ALA. March 1, 2022: What if your teenage son went off to war — fought in one battle — died in that battle — and then you find out his death was actually after the war had ended — AND your side lost the war? Today, we would say parents of these dead soldiers would have complicated grief. Indeed.

FORT BLAKELEY, ALA. March 1, 2022: What if your teenage son went off to war — fought in one battle — died in that battle — and then you find out his death was actually after the war had ended — AND your side lost the war? Today, we would say parents of these dead soldiers would have complicated grief. Indeed.

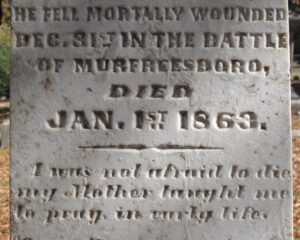

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be?

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be? Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride.

Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride. Was conscious

Was conscious The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

“Charlie” was not a very creative name, but it just seemed to fit a male King Charles Spaniel. At first, we crated him at night. After weeks of barking, he finally settled into his crate and his place at home. Until…

“Charlie” was not a very creative name, but it just seemed to fit a male King Charles Spaniel. At first, we crated him at night. After weeks of barking, he finally settled into his crate and his place at home. Until… Charlie joined Katie in Oxford her second year at Ole Miss, where he supported her during roommate issues and dating cycles. Their deep bond reached new depths. A dog just loves unconditionally.

Charlie joined Katie in Oxford her second year at Ole Miss, where he supported her during roommate issues and dating cycles. Their deep bond reached new depths. A dog just loves unconditionally.

On Sunday afternoon, my wife and I were pulling into the Walmart parking lot, and she blurted out, “Katie has to come home tonight.” It was a mother’s flash of insight for her soon-to-be grieving daughter. She called Katie and told her to get to National airport and get on a plane. I picked her up in Memphis with Charlie a few hours later. They slept together on our bedroom floor that night before she returned to D.C., Monday. In the car on the way to the Memphis airport, she “Snapped” a photo to friends, “my last photo I’ll ever take with my baby.” Indeed, it was.

On Sunday afternoon, my wife and I were pulling into the Walmart parking lot, and she blurted out, “Katie has to come home tonight.” It was a mother’s flash of insight for her soon-to-be grieving daughter. She called Katie and told her to get to National airport and get on a plane. I picked her up in Memphis with Charlie a few hours later. They slept together on our bedroom floor that night before she returned to D.C., Monday. In the car on the way to the Memphis airport, she “Snapped” a photo to friends, “my last photo I’ll ever take with my baby.” Indeed, it was.

I was here to ponder how one place can hold so much grief and healing.

I was here to ponder how one place can hold so much grief and healing.

It turns out her idea was masterful. The Wall has become a place of reflection and healing, a public place to grieve privately. Annually, millions walk the path by the wall in silence, as if in a sacred space — indeed it is. Grown men weep as they touch the name of a fallen comrade. Children visit the names of fathers they never knew.

It turns out her idea was masterful. The Wall has become a place of reflection and healing, a public place to grieve privately. Annually, millions walk the path by the wall in silence, as if in a sacred space — indeed it is. Grown men weep as they touch the name of a fallen comrade. Children visit the names of fathers they never knew. The story is about loss and backpacking, two abiding interests in my life. I’d probably write favorably of anyone who takes their grief on a 1,100-mile backpacking trip. Cheryl Strayed did and wrote about it.

The story is about loss and backpacking, two abiding interests in my life. I’d probably write favorably of anyone who takes their grief on a 1,100-mile backpacking trip. Cheryl Strayed did and wrote about it. There are many moving passages in the book, but I was caught by one line on the next-to-last page of the book. Cheryl touches the bridge on the Columbia River, the site at the end of her journey. She walks back to an ice cream stand to buy herself a treat with the last two dollars she has to her name. She enjoys her ice cream, chatting with a lawyer from Portland who stops for ice cream, too. She says goodbye to him and

There are many moving passages in the book, but I was caught by one line on the next-to-last page of the book. Cheryl touches the bridge on the Columbia River, the site at the end of her journey. She walks back to an ice cream stand to buy herself a treat with the last two dollars she has to her name. She enjoys her ice cream, chatting with a lawyer from Portland who stops for ice cream, too. She says goodbye to him and