Would you spend $100,000 on a cancer treatment with many painful side effects that might help you survive 6.24 months as opposed to 5.91? That is 10 days longer in greater pain and suffering?

What if the doctor told you just that “this treatment will help you survive longer”? This is a true statement even though you might only survive 5.6% longer. That IS longer.

I have just discovered two great videos with Dr. Michael Greger discussing this very topic. Each video is less than seven minutes and worth every minute of your time. One is called “How Effective is Chemotherapy?” and the other is “How Much Does Chemotherapy Improve Survival?”

I have just discovered two great videos with Dr. Michael Greger discussing this very topic. Each video is less than seven minutes and worth every minute of your time. One is called “How Effective is Chemotherapy?” and the other is “How Much Does Chemotherapy Improve Survival?”

Let me be clear. I have no idea what I would do if I had a cancer diagnosis. I have close friends and family members who had advanced cancers and have been treated very successfully and are living active lives years after their treatments.

On the other hand, I have had patients, and, again, close friends and family members who received brutal chemotherapies and died. Many of those seemed to have received no benefit from their treatments and suffered great burdens. Many patients go bankrupt in order to pay for treatments.

Dr. Greger, in the first video says, “A large proportion of cancer patients reported their willingness to declare bankruptcy or sell their homes to pay for treatment. I mean, look, aren’t the high prices justified if new and innovative treatments offer significant benefits to patients? But you may be shocked to find out that many FDA-approved cancer drugs might lack clinical benefit.”

In his second video he referred to a study reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. “In fact, the most expensive drug they looked at, the one costing $169,836 a year, did not improve overall survival at all, and actually worsened quality of life. That’s $169,000 just to make you feel worse with no benefit. Why pay a penny for a treatment that doesn’t actually help?”

In his second video he referred to a study reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. “In fact, the most expensive drug they looked at, the one costing $169,836 a year, did not improve overall survival at all, and actually worsened quality of life. That’s $169,000 just to make you feel worse with no benefit. Why pay a penny for a treatment that doesn’t actually help?”

I am NOT giving medical advice here. I am encouraging all of us to ask questions of our physicians. If a recommended therapy is said to improve survival, ask, “How much improvement?” Is it just 10 days over six months while suffering uncomfortable side effects? Ask about cost. Would I be willing to spend my financial legacy for those 10 days?

This all reminds me of the importance of our own emotional and spiritual preparation for dying. When “our time” comes we will be ready to die… or be healed. Either way, we’re okay.

________________________________________

Cover Photo by Marcelo Leal on Unsplash

Chaplain Hank Dunn is the author of Hard Choices for Loving People: CPR, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures and the Patient with a Serious Illness and Light in the Shadows. Together they have sold over 4 million copies. You can purchase his books at hankdunn.com or on Amazon.

I was leaving on one of my daily bike rides recently and needed to pick a new book to listen to. I selected a reread —

I was leaving on one of my daily bike rides recently and needed to pick a new book to listen to. I selected a reread —  “No one ever told me that grief felt so much like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid.”

“No one ever told me that grief felt so much like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid.” “It is incredible how much happiness, even how much gaiety, we sometimes had together after all hope was gone.”

“It is incredible how much happiness, even how much gaiety, we sometimes had together after all hope was gone.”  I was such a scaredy-cat at 8 years old. All I can remember of two particular movies in 1956 was that I kept my eyes closed during the entirety of each film. I have just discovered, through Wikipedia, that

I was such a scaredy-cat at 8 years old. All I can remember of two particular movies in 1956 was that I kept my eyes closed during the entirety of each film. I have just discovered, through Wikipedia, that  I just placed the latest “deep field” photo from the new James Webb Space Telescope to my home screen on my iPhone. This is a time exposure photo of a portion of the night sky the size of a grain of sand held at arms-length. Thousands of galaxies appear as we look back billions of years. Each galaxy has billions of stars — each star is not unlike our sun.

I just placed the latest “deep field” photo from the new James Webb Space Telescope to my home screen on my iPhone. This is a time exposure photo of a portion of the night sky the size of a grain of sand held at arms-length. Thousands of galaxies appear as we look back billions of years. Each galaxy has billions of stars — each star is not unlike our sun. I lived a few doors down from Scott and his family for four years. His sisters babysat my kids. I was Scott’s den leader in Cub Scouts. As disease ravaged his young body, Scott graduated from college in a wheelchair. I was so privileged to be a part of his care.

I lived a few doors down from Scott and his family for four years. His sisters babysat my kids. I was Scott’s den leader in Cub Scouts. As disease ravaged his young body, Scott graduated from college in a wheelchair. I was so privileged to be a part of his care.

This is how David Brooks starts a recent

This is how David Brooks starts a recent  Gradually, for some people, a new core narrative emerges answering the question, “What am I to do with this unexpected life?” It’s not that the facts are different, but a person can step back and see them differently. New frameworks are imposed, which reorganize the relationship between the events of a life. Spatial metaphors are helpful here: I was in a dark wood. This train is not turning around. I’m climbing a second mountain.

Gradually, for some people, a new core narrative emerges answering the question, “What am I to do with this unexpected life?” It’s not that the facts are different, but a person can step back and see them differently. New frameworks are imposed, which reorganize the relationship between the events of a life. Spatial metaphors are helpful here: I was in a dark wood. This train is not turning around. I’m climbing a second mountain.

Judith Graham

Judith Graham

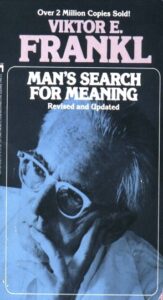

“The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action.… Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.… We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

“The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action.… Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.… We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. I’ve had the opportunity to officiate many funerals over the years. This was supposed to be one of the “easy” ones. The dead man’s family had a relative who once was a member of my church in Vienna, Virginia, back in the day. None of the family attended that church now — or any church. So, when the man died suddenly of a heart attack at 64, they turned to us for a minister to conduct the service — kind of a rent-a-preacher.

I’ve had the opportunity to officiate many funerals over the years. This was supposed to be one of the “easy” ones. The dead man’s family had a relative who once was a member of my church in Vienna, Virginia, back in the day. None of the family attended that church now — or any church. So, when the man died suddenly of a heart attack at 64, they turned to us for a minister to conduct the service — kind of a rent-a-preacher.

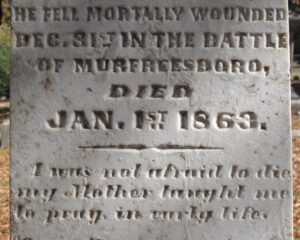

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be?

A young soldier named William Gaston Barringer turned 18 on October 5, 1862. Less than three months later, he was wounded and died as a prisoner of war 200 miles from home. Yet, there is evidence he had a good death. How could this be? Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride.

Plagues in the 1300s killed 40-60% of the European population. Such widespread death led to the release of a couple of books known as the Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”). These were Christian instructions on how to have a good death. There were accompanying woodcuts, like one showing demons tempting the dying man with crowns symbolizing earthly pride. Was conscious

Was conscious The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.

The words on Barringer’s marker were an assurance to his family that he died a good death: “I was not afraid to die; my Mother taught me to pray in early life.” These seem like the dying words of a conscious man.